Almost every child learns that the people in the mirror wear their watches on their right hands, or that ‘mirror writing’ is ‘flipped’ ‘left to right’, or something like that. Looking more closely at the concept of left and right, it becomes apparent that this cannot truly be the case – so why do we almost all ‘learn’ something like this?

Imagine we find some kind of space-time anomaly which enables us to communicate with a newly-met civilisation many light years away, via digital streams of information. Let’s say we somehow figure out how to agree on the concept of a pixelated image consisting of rows and columns of dots which emit various frequencies of light – or colours. To enrich our communication, we now plan to exchange pictures, encoded into streams of data describing each pixel in turn. How will we explain to them that they should lay out the rows of colour pixels from top to bottom, and from left to right? Perhaps we can agree that the local gravitational field in which the aliens live provide a reference for ‘top to bottom’, which feels somewhat important for at least some images – we don’t want to give the impression that we hop around on our heads, for example. Explaining left and right is much trickier. Fortunately, left and right are less often critical to the interpretation of a picture, but the point is that there is no direct way to explain what we mean by this, if all we have is a stream of pulses by which to communicate.

Sneaky theoretical physicists may propose moving the conversation to neutrinos – those ghost-like particles which are emitted by stars like our sun, and which ooze through us at a rate of trillions per second without ever posing much of a threat to our health because they largely fail to interact with anything. Neutrinos have weird properties relating to how they tend to ‘spin’, whatever that means – and it doesn’t mean anything very similar to what Muthia Muralitharan was so good at doing with a cricket ball in his heyday. Nevertheless, neutrinos have a preference for ‘spinning’ one way rather than another, from the perspective of the direction in which they are moving, and a suitably long conversation about neutrinos might crack this conundrum of explaining left and right without sitting in the same room and simply demonstrating it. It does feel a bit like cheating, though: a bit like saying we’ve explained green because we passed someone a piece of green paper. Try explaining green to someone to whom you can’t show a green object!

This might leave us thinking that the concept of left and right is somewhat arbitrary. A mirror is just a piece of flat glass with a layer of silver on one side, and it can’t really interact with the world in any way that connects with what we think of as left and right. Why would a mirror flip left and right instead of up and down? An undergraduate physics teacher once told us that mirrors don’t turn left into right and vice versa – but that they turn left-handed coordinate systems into right-handed coordinate systems, and vice versa, but this is wordplay and also doesn’t explain anything.

To get to the bottom of this, we need to understand what we mean, geometrically, by things like ‘translation’, ‘reflection’ and ‘rotation’, and it’s easier to start with two dimensional pictures. In fact, we will stick with two dimensional pictures for this entire article, and then consider the fully three dimensional case later.

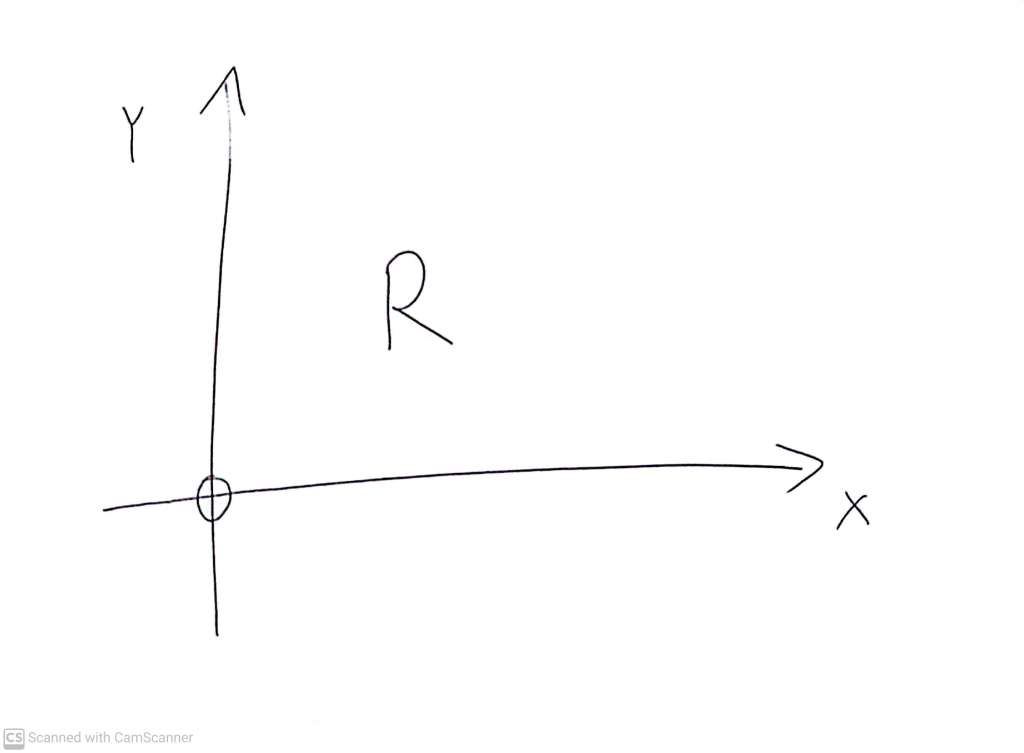

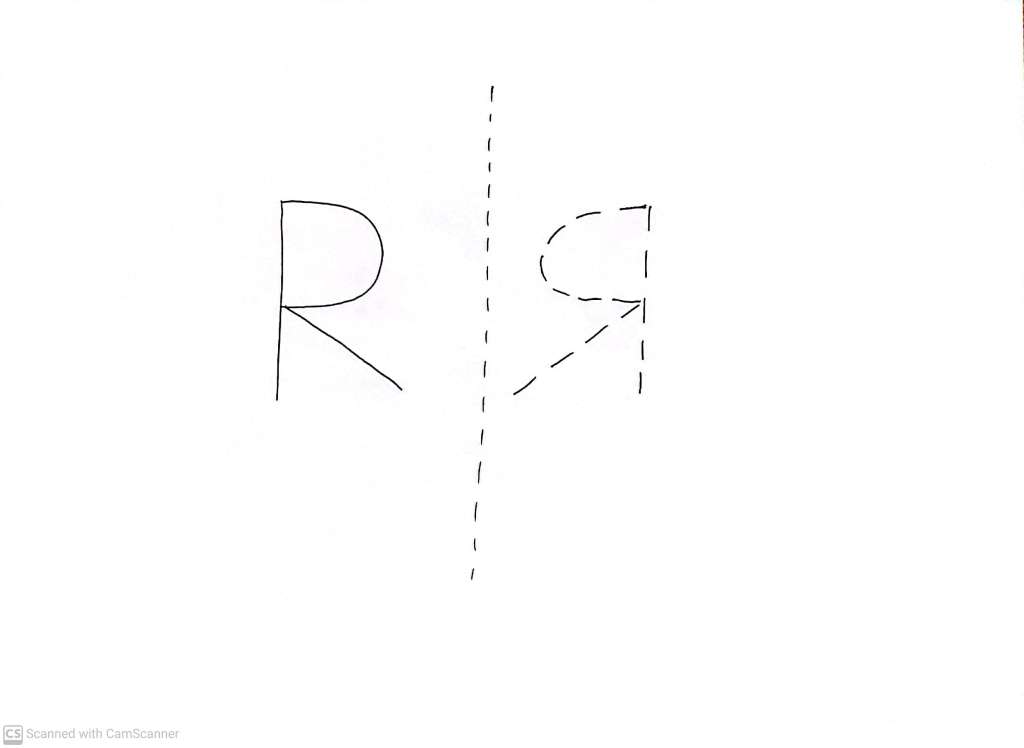

Here is a shape, the letter R, drawn in an X-Y coordinate system with the origin (the point where X=0 and Y=0) at the intersection of the drawn axes, and the ‘positive’ direction of each axis being the one which has the arrow.

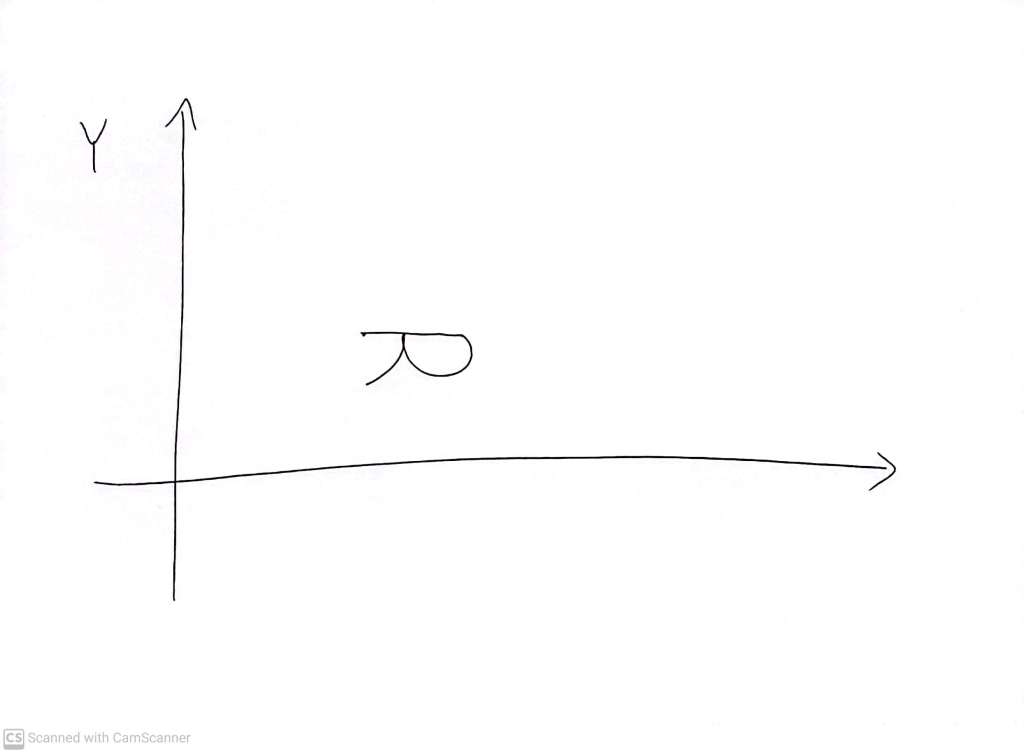

Here is that shape, having been ‘translated’ – i.e moved, as is, without changing its shape, orientation or size (even if it looks a little smaller), to another location

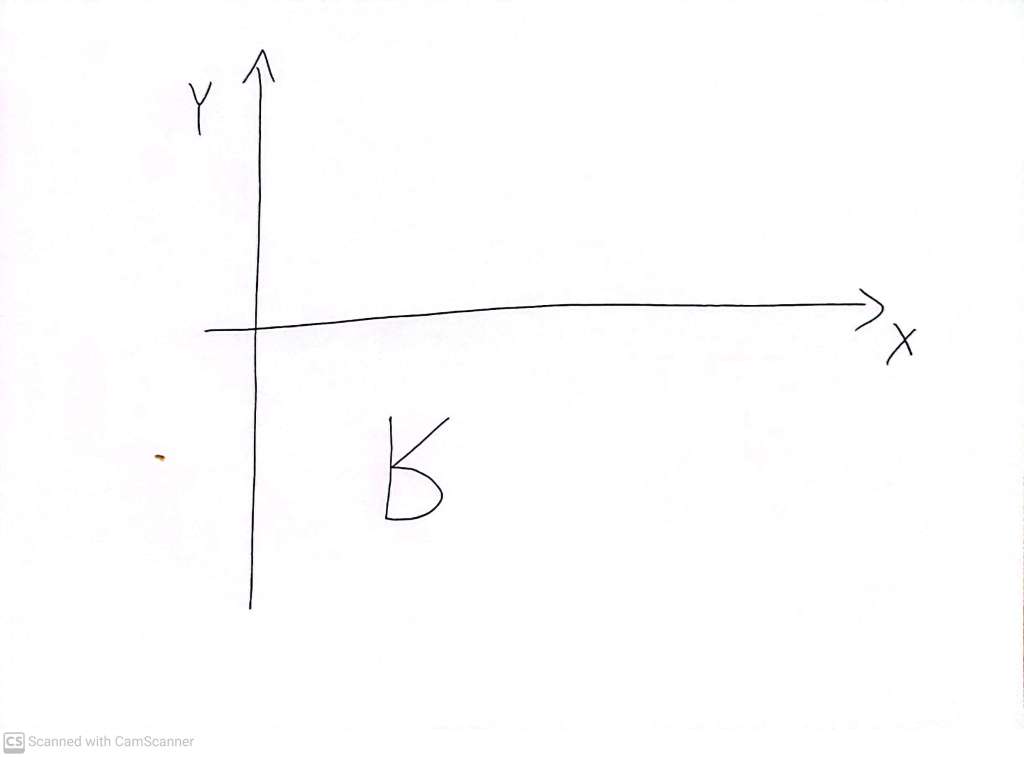

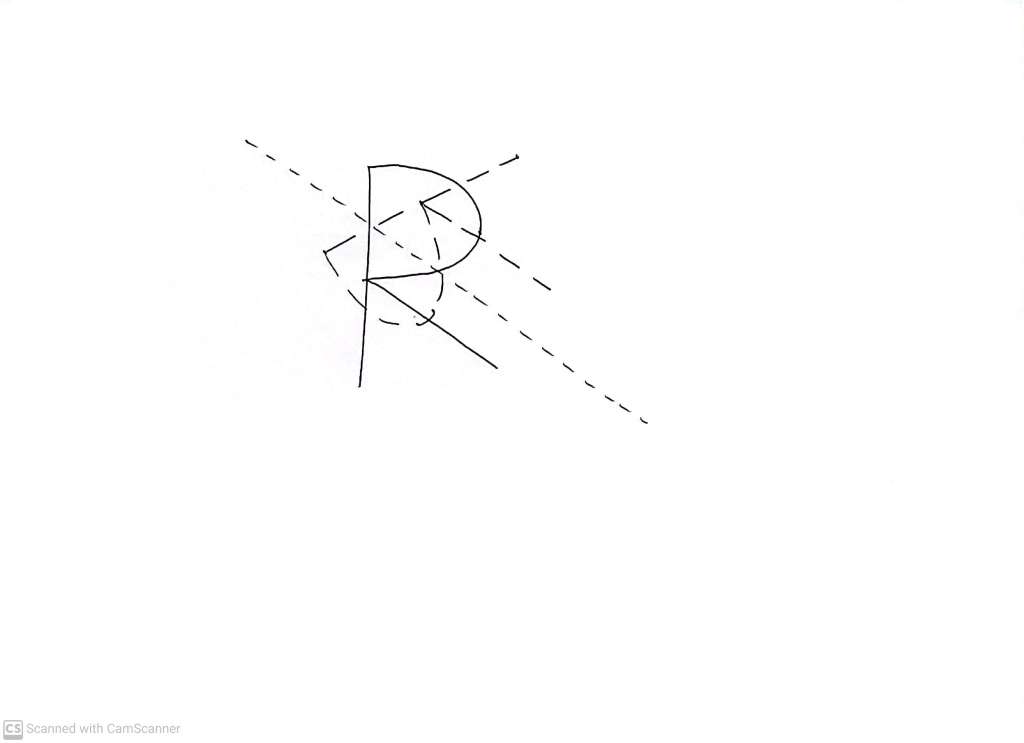

Here it is rotated, ‘clockwise’, by a quarter turn, around an ‘axis’ centred on the bottom left of the shape, without specifically meaning to apply any particular ‘translation’ – but again the diagrams are not very precise.

Now here is the original shape ‘reflected’ ‘along the X axis’, or, said differently but meaning the same thing, ‘through the Y axis’

by which we apparently mean something like this:

- Locate each point on the shape (yes, there are infinitely many points, and we have to simultaneously do this to ALL of them, otherwise we’ll never be done)

- Find its X and Y coordinates – (X,Y)

- Relocate the point to the location (-X,Y)

So, if we want to reflect our original shape ‘along the Y axis’ (alternatively phrased as ‘through the X axis’) we get:

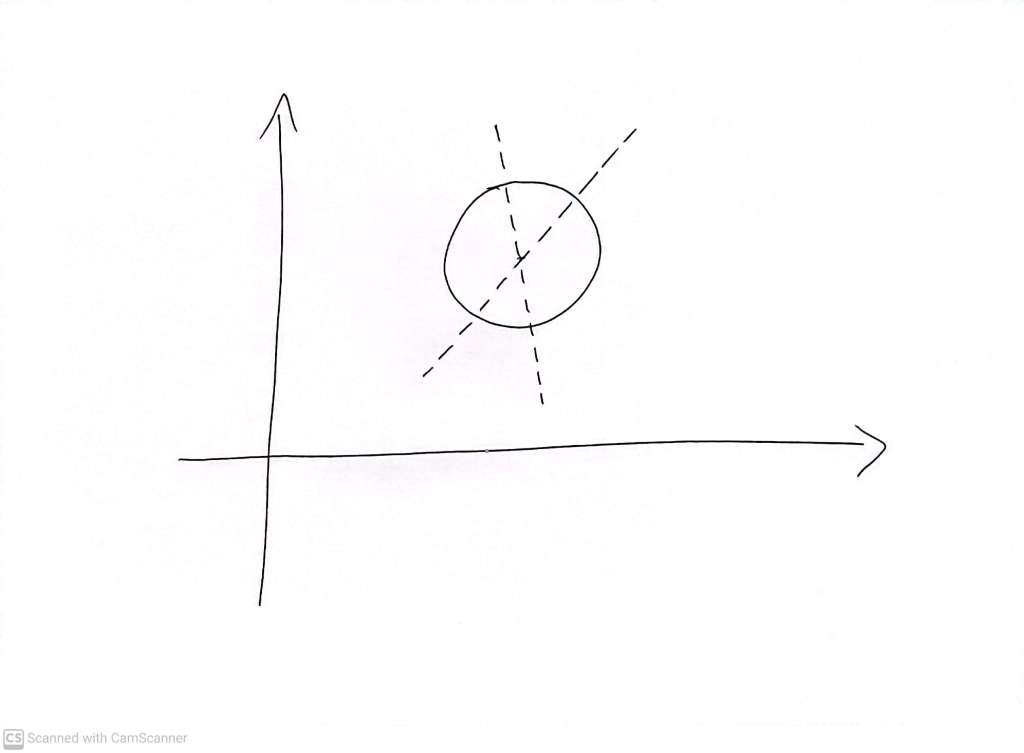

In this case we can call the X axis our ‘mirror line’. In the three dimensional space of our ordinary daily existence, we usually think of a mirror as living in a plane – we are not discussing curved mirrors here. This is where we are headed, but we are not ready to discuss mirror planes just yet. Now, for some shapes, we can’t really tell a rotation from a reflection, or from doing nothing at all. For example, a circle:

This picture looks the same after we rotate the circle, by any angle, around its centre. It also looks the same if we reflect it along any ‘mirror line’ that passes through the centre – for example one of the two dashed lines in the picture. We say that a circle is ‘invariant under’ these ‘transformations’ – meaning it looks the same before as after.

If we start with a square:

We will notice a rotation if it is not a multiple of a quarter turn, like:

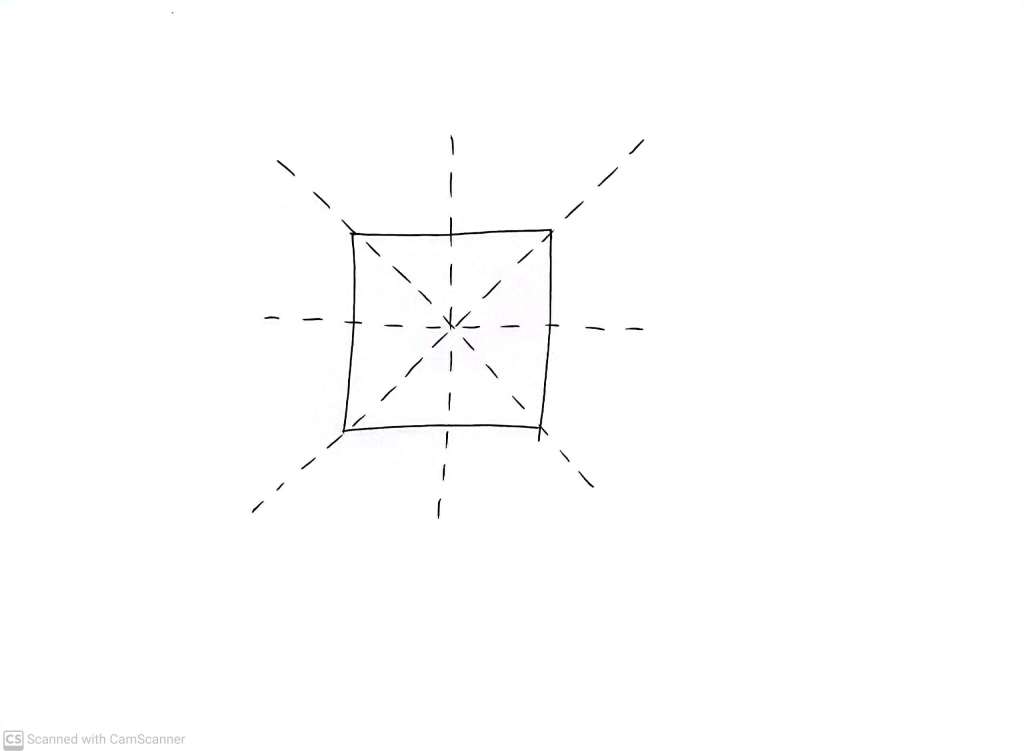

And we will notice a reflection unless it is ‘through’ one of the dashed lines shown here

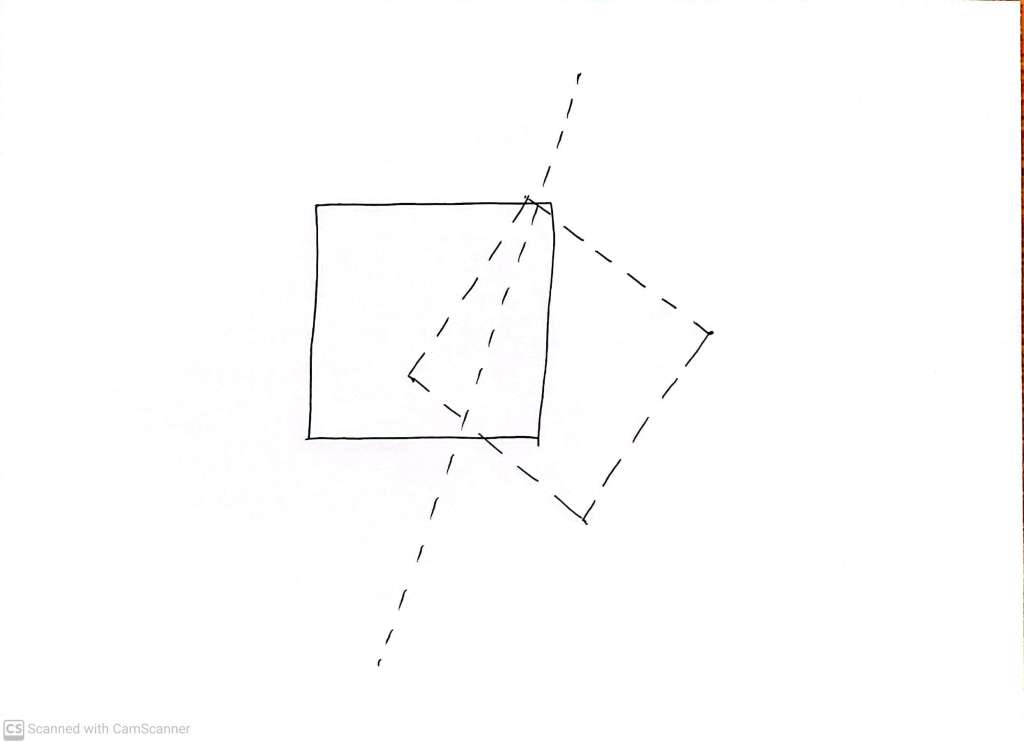

For example, the solid line square below is reflected through the short-dash mirror line, giving us the longer-dash ‘reflected’ square.

So now we can ask – does a ‘reflection’ ‘change anything’ about our R shape?

And does this depend on which ‘mirror line we choose

Basically, the question is this: Can we ‘rotate’ and/or ‘translate’ the ‘reflected’ shape in such a way that we get back to where we started – crucially without relying on using another ‘reflection’. For squares and circles, this is easy. No matter how we choose the mirror line through which to reflect a square or circle, we always end up with a square or circle which is, in essence, exactly the same as the one we started with. I say ‘in essence’, to mean that the reflection, which might be tilted or displaced relative to the original, can be repositioned on to the original square without having to sneakily explicitly undo the reflection – relying only on translation and rotation.

Now a reflected R cannot be ‘rotated’ and ‘translated’ to make it ‘look like’ (i.e. hide by lying precisely on top of) the original R. A reflected R is not the same thing as a normal R.

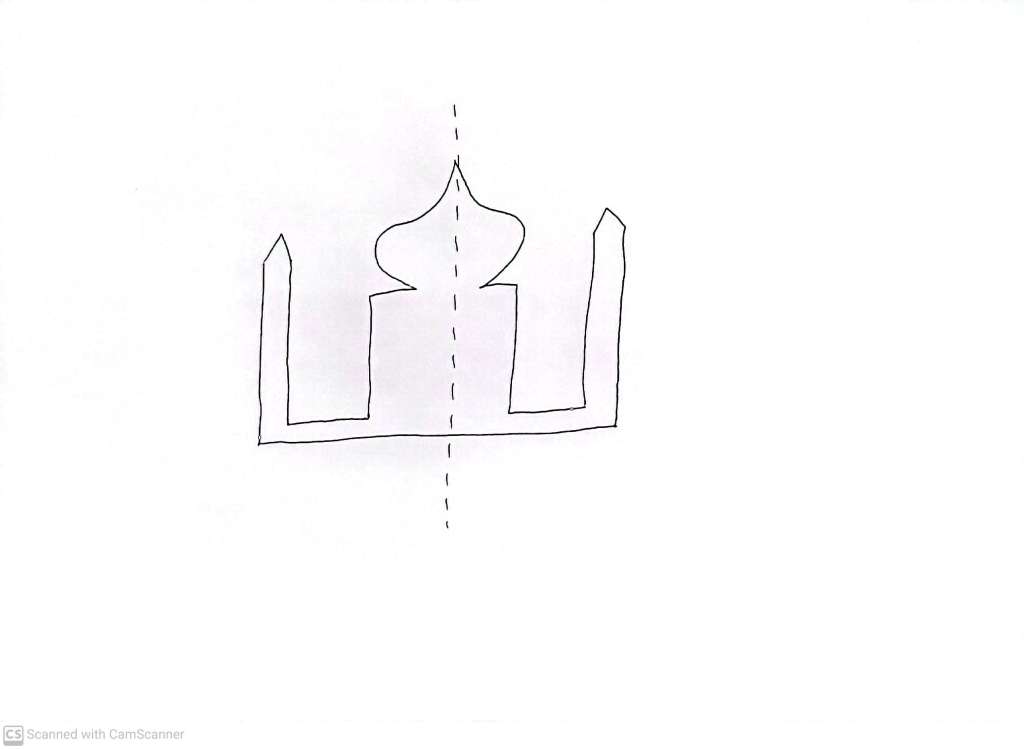

You have to do something special in order to draw a shape which looks ”essentially the same” after reflection. Technically, we say such a (2 dimensional) shape has a line of ‘reflection symmetry’ or ‘mirror symmetry’. We can cut to the chase and forget about mucking around with translations and rotations after doing some crazy reflections – all we need to do, to convince ourselves that there is mirror symmetry, is just demonstrate that there is a particular reflection which has no effect. In informal language, this is pretty much what is usually meant by saying the shape “is symmetrical”, or “has symmetry”, like a symmetrical building.

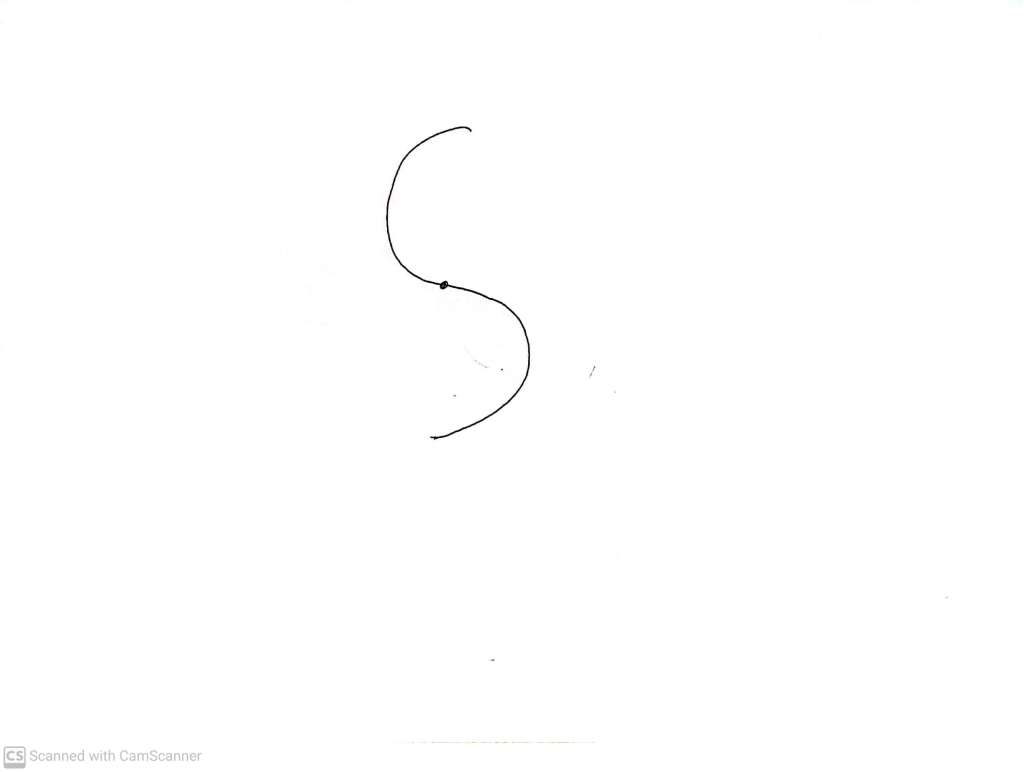

Mathematicians like to think of a whole lot of other situations as also showing things to ‘have symmetry’. Most simply, consider this shape:

It has no ‘mirror lines’ of symmetry. However, if you rotate it by (any multiple of) half a turn, around the central point, it looks the same as before. This is a kind of ‘rotational’ symmetry. An equilateral triangle has both mirror symmetry and 3 fold ‘rotational symmetry’. Another trivial example is an infinitely long line occupying all the points in a cartesian plane which have a particular value of Y:

If we ‘translate’ (nudge without rotating it) the line left or right, parallel to the X axis, by any amount whatsoever, we get back the same infinite line. A line, then, has arbitrary ‘translational symmetry’ in the direction along which it lies. There are other interesting details about all sorts of symmetries, but we don’t need to discuss all that now.

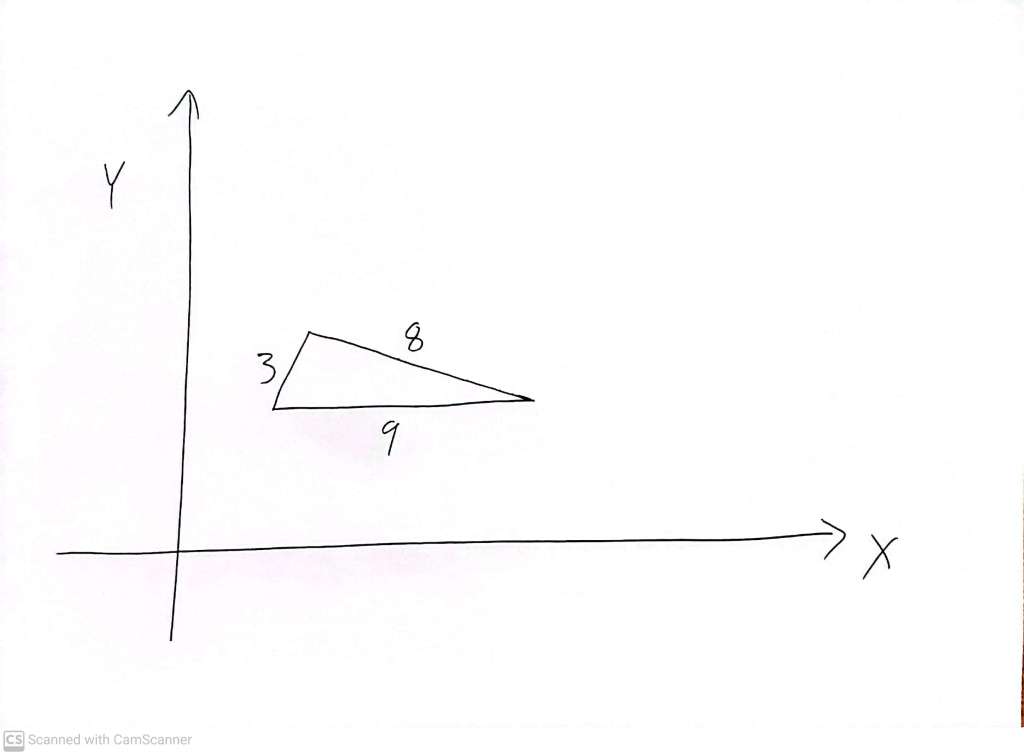

One last aside: in school we learn about ‘congruent’ triangles. We learn that two triangles are congruent, if (and only if) the lengths of the three sides of one triangle are equal to the lengths of the sides of the other triangle. There is usually some discussion about why we would introduce this term ‘congruent’, and how it differs from saying two triangles are equal. Well, imagine a triangle with sides of length 3, 8 and 9 centimetres.

(Please note: you may wonder, based on my diagram, whether there is a ‘right angle’ in this triangle. There is not, even if my drawing looks like this might be the case. The angle that is close to a right angle is in fact supposed to be slightly larger than a right angle. It is incredibly important not to think that one can ‘see’ crucial details in rough diagrams.)

Now imagine a tiny person walking around the triangle on the page on which it is drawn, noting that the diagram shows what we see when we look ‘down’ at the page, not when looking up at it from below – these details matter. Let the walk start somewhere on the shortest side, with the little person keeping the interior of the triangle on their left. After the shortest side comes the longest, and then the one of middle length. If we reflect this triangle through the X axis, we get

The reflected triangle is ‘congruent’ to the one we started with, because the process of reflection does not change the length of any side. But, they are not identical. If the tiny person we just discussed above walks around the reflected version of the triangle on this same page, again starting on the shortest side and again keeping the interior of the triangle on their left – then the next side encountered is the one of middle length, and only then the longest side. This triangle has no mirror symmetry, and its reflection, though congruent to it, cannot be rotated to give the appearance of two fully ‘equal’ shapes. With fully equal shapes, you can exactly hide the one under the other.

So now we have some deeper understanding of the known observation that some letters will look different, and some will not, if they are subjected to ‘reflection’ perpendicular to ‘mirror lines’ which ‘lie on the plane’ in which the letters lie. But this is not quite what is happening when we look in a plane mirror in a three dimensional room. To understand that fully, we will have to walk right through the proverbial looking glass – and that is the subject of a separate chapter.

One response to “Reflections on Reflections, Part One”

[…] is part two of a discussion started in the previous post – and it may not make complete sense if this one is read first. We’re trying to figure out how […]