Continuing our reflections on reflections – but now also in three dimensions!

This is part two of a discussion started in the previous post – and it may not make complete sense if this one is read first. We’re trying to figure out how it is that the person in the mirror appears to be wearing their watch on the opposite hand as the person looking into the mirror, or indeed whether this is the right way to describe what is happening.

In part one, we explored, in two dimensions, how a reflection ‘across’ a ‘mirror line’ transforms a typical object/shape (of low symmetry) into something that cannot be ‘rotated’ and ‘translated’ to give back the original shape. Sometimes these two versions of the shape are said to be ‘congruent’, indicating they are equivalent for some purposes, but not necessarily identical (identical shapes are also congruent). For some shapes, the reflected version CAN be rotated until it once again looks exactly like the original shape. We say that such a shape/object is ‘invariant under reflection’, or that is possess ‘mirror symmetry’. This is what we most commonly mean when we colloquially say something ‘is symmetrical’.

Now let’s bump it up to three dimensions.

The setup

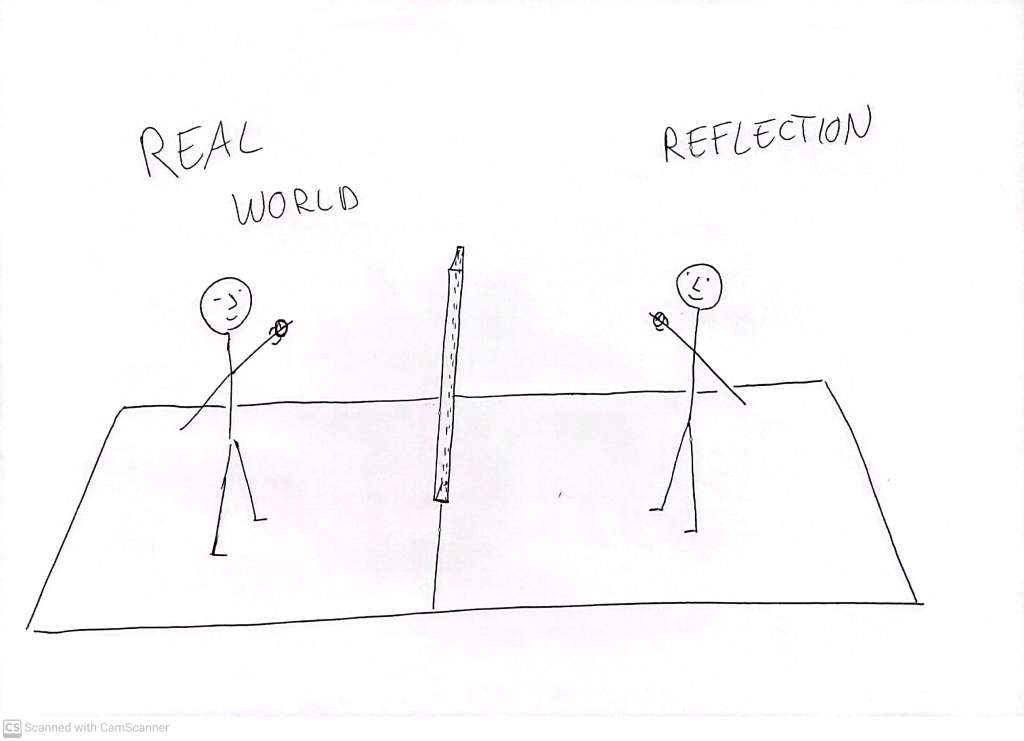

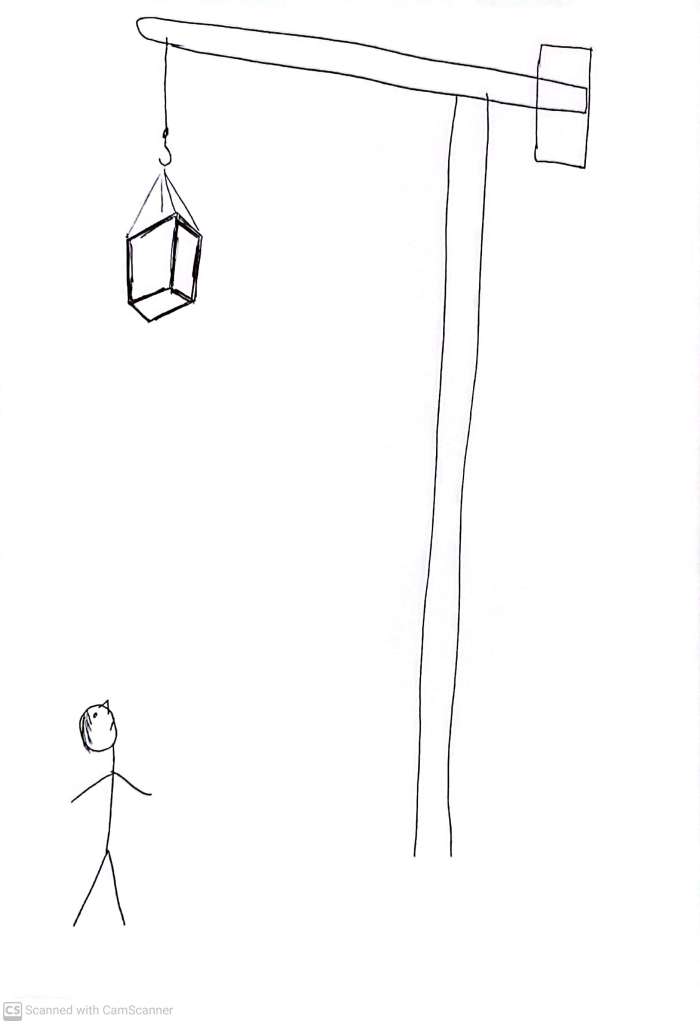

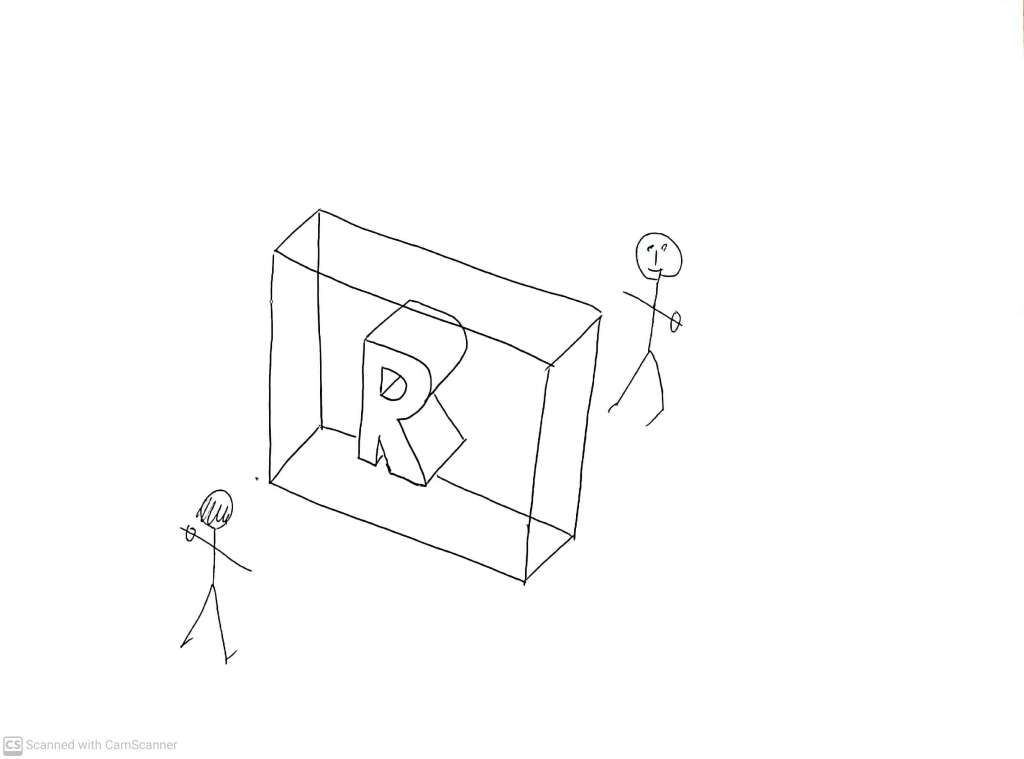

If we imagine having a edge-on view of a large mirror, and we imagine being able to see both 1) a ‘real world’ room, and 2) its reflection, as if they were equally present in our field of view, we might visualise something like this:

In this picture, it is not hard to see how one might talk of the ‘real’ person having a watch on their left hand, while the ‘reflected’ person has a watch on their right hand – but does this really make sense? Coffee in hand, let’s jump in

Defining coordinates

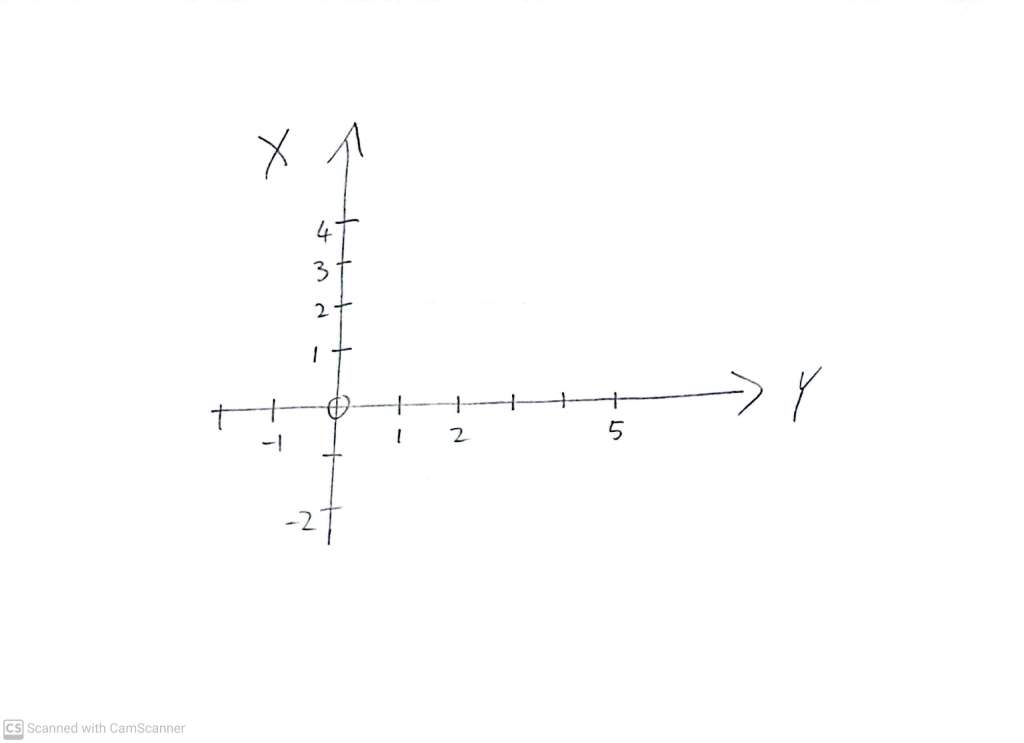

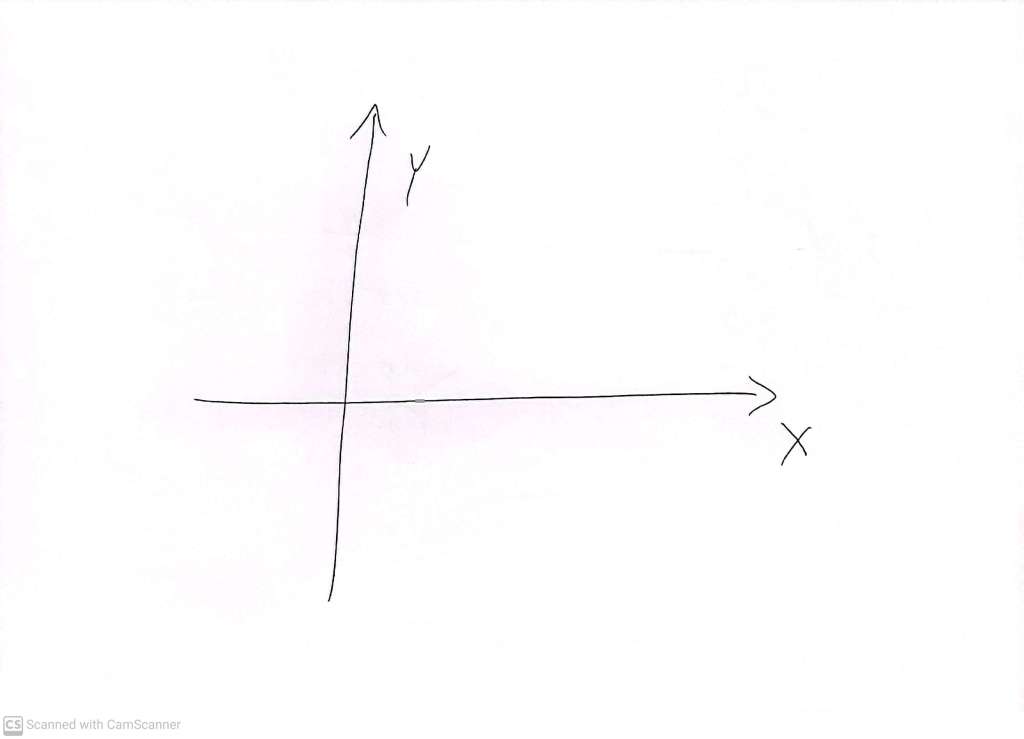

Our investigation is fundamentally about coordinate systems. Most of us are familiar with the two dimensional (X,Y) coordinate system called the cartesian plane:

From now on, we will use arrows to indicate in which direction the ‘positive’ side of an axis lies, without necessarily labeling positive and negative values.

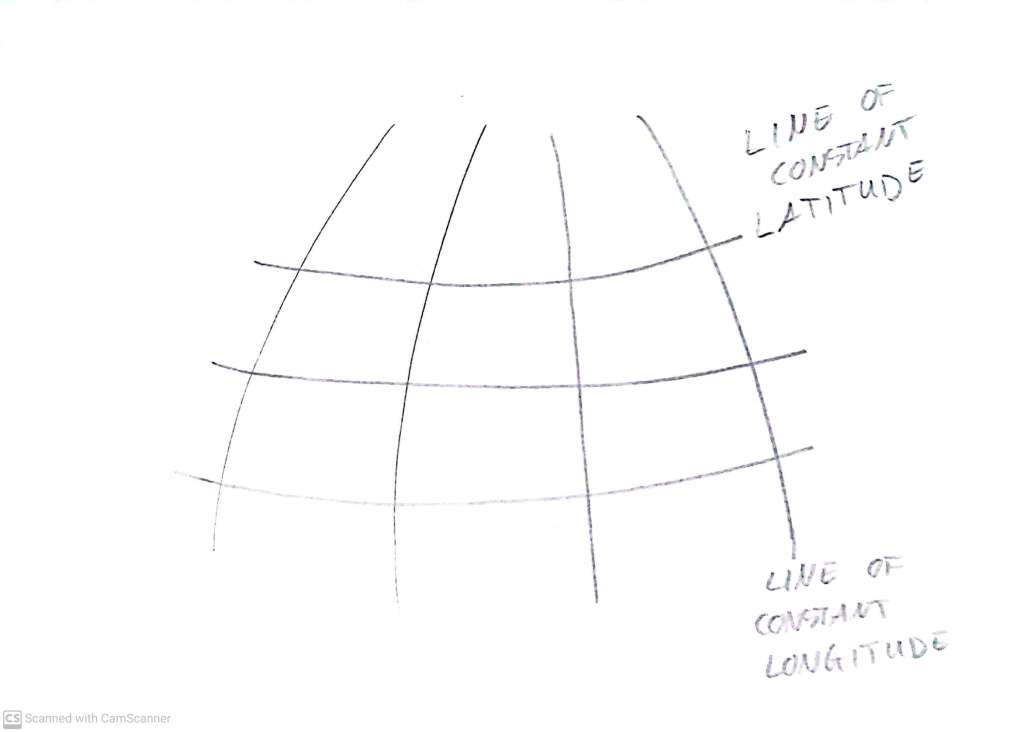

Most of us have done a little bit of reading of maps, using latitude (North/South) and longitude (East/West). The fact that the surface of the earth covers a sphere, i.e. is not an infinitely large flat sheet, does indeed have its consequences – but when we look at a small piece of the earth, navigating on the ground is just like navigating a two-dimensional cartesian plane.

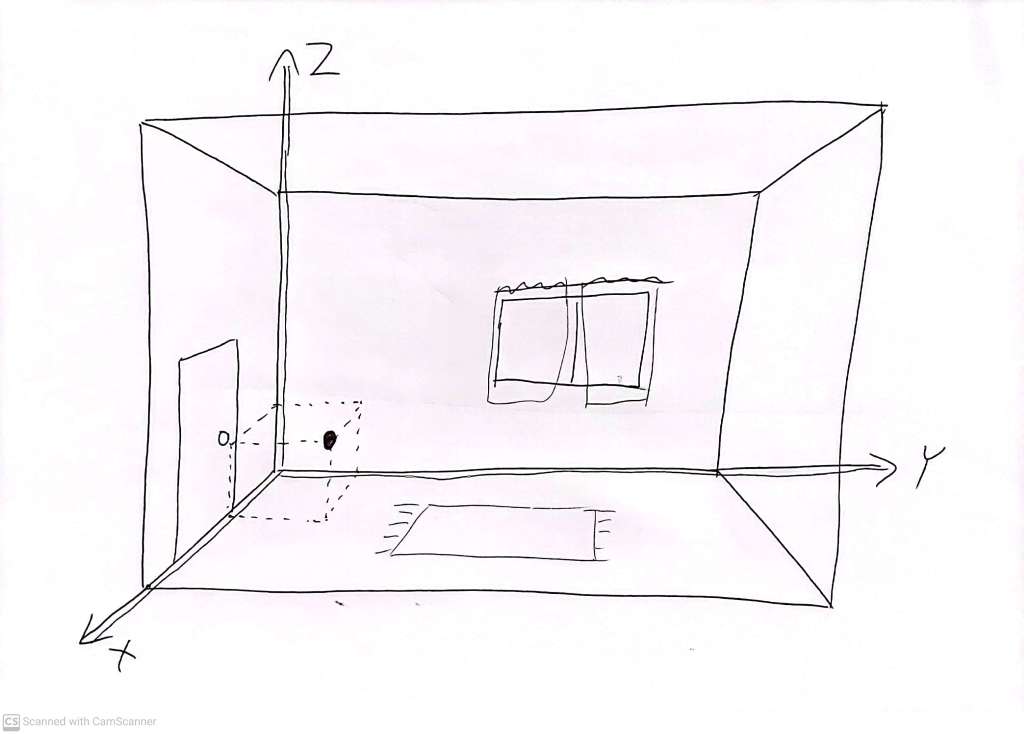

In three dimensions, we need an additional coordinate. One simple way to understand this is to think of locating a point in a room. We can label three edges of the room (two where walls meet the floor, one where these two walls meet) to indicate the X, Y and Z coordinates, with the corner of the room being ‘the origin’ – i.e. the point with coordinates (X=0, Y=0, Z=0).

We can specify the coordinates of any point in that order (X,Y,Z). The black dot has location (1,1,1) and the location of the point 1 unit of distance away from the origin, along the X axis is (1,0,0):

The point (1,2,3) can be visualised as

and so on.

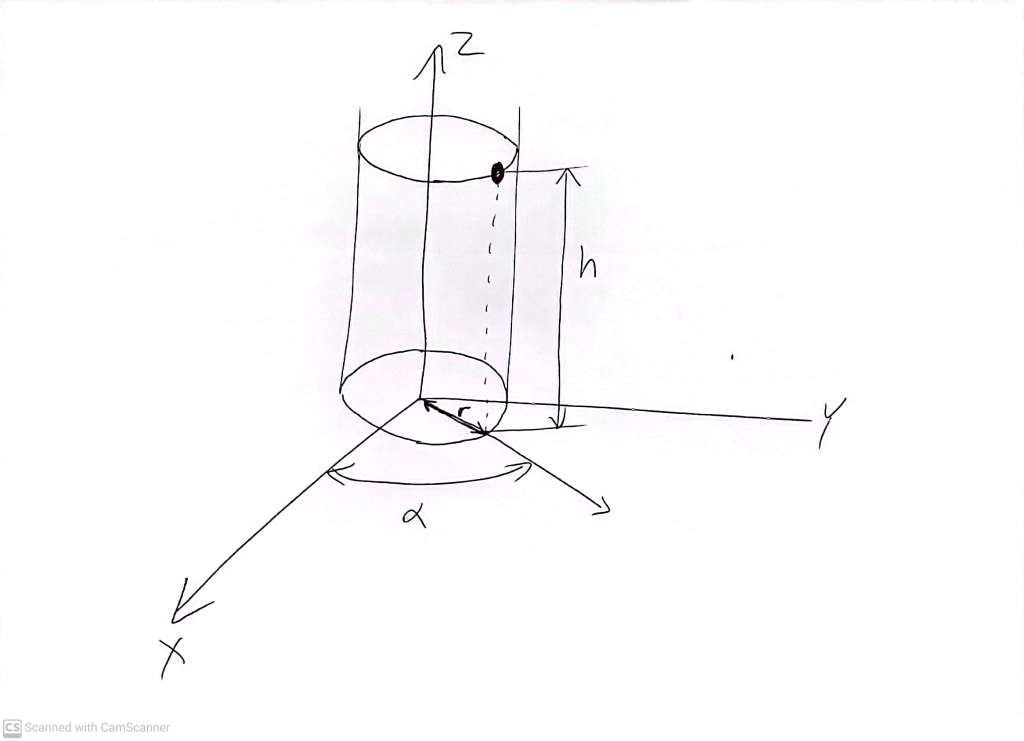

Just as latitude and longitude coordinates are not purely rectangular (in their case, because the entire 2 dimensional region they are supposed to describe is itself not flat) so we can use all sorts of interesting coordinate systems, including curved coordinate systems, to describe three dimensional space. For example, in cylindrical coordinates

we label a position by:

- a distance from the Z axis, r

- a height above the XY plane, h, also equivalent to the usual Z coordinate)

- an angle, here labelled with the greek letter alpha (α) relative to the X axis, suitably carefully defined

Here we are just going to work with ‘rectangular’ coordinate systems like the one we just built by following our nose.

Once you have chosen the X and Y axes, the line on which the Z axis will lie is already determined – it lies perpendicular to the ‘X-Y plane’. But which way is positive and which is negative? It’s up to us – there is no right or wrong answer.

Defining directions in two dimensions

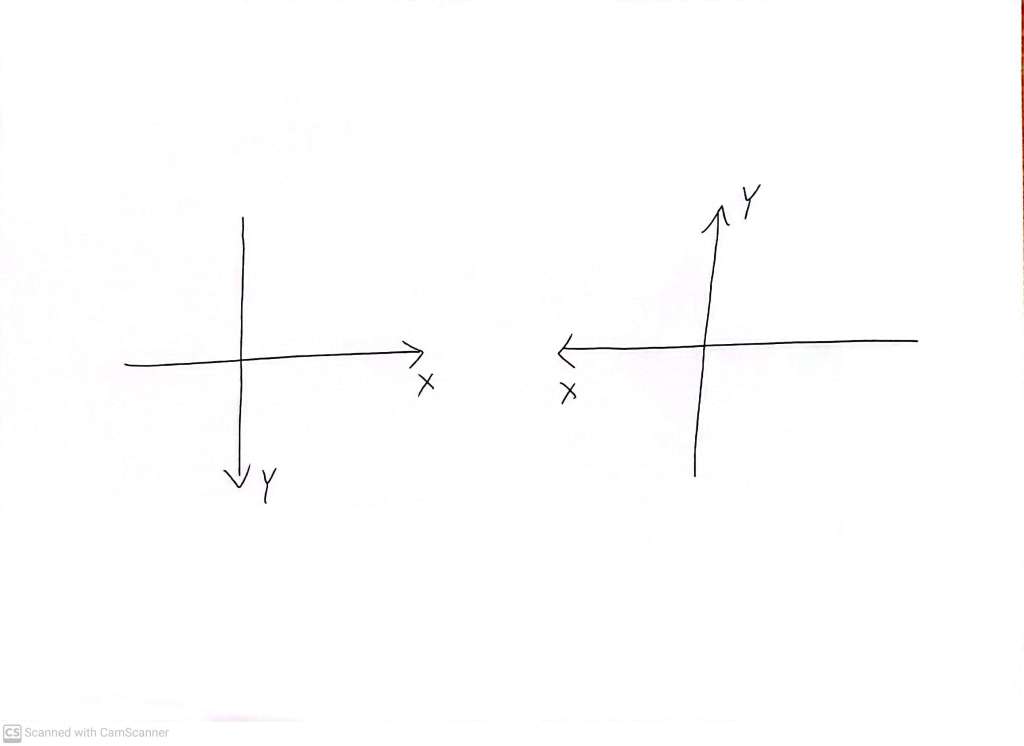

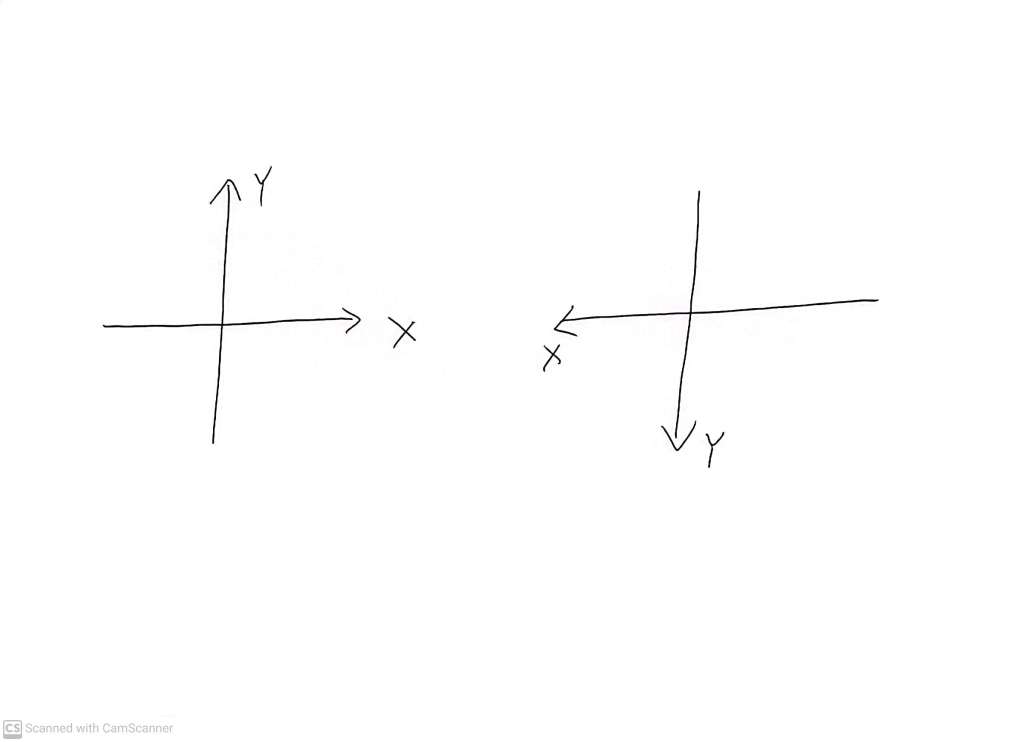

There is no deep reason why we almost always draw two dimensional systems like this:

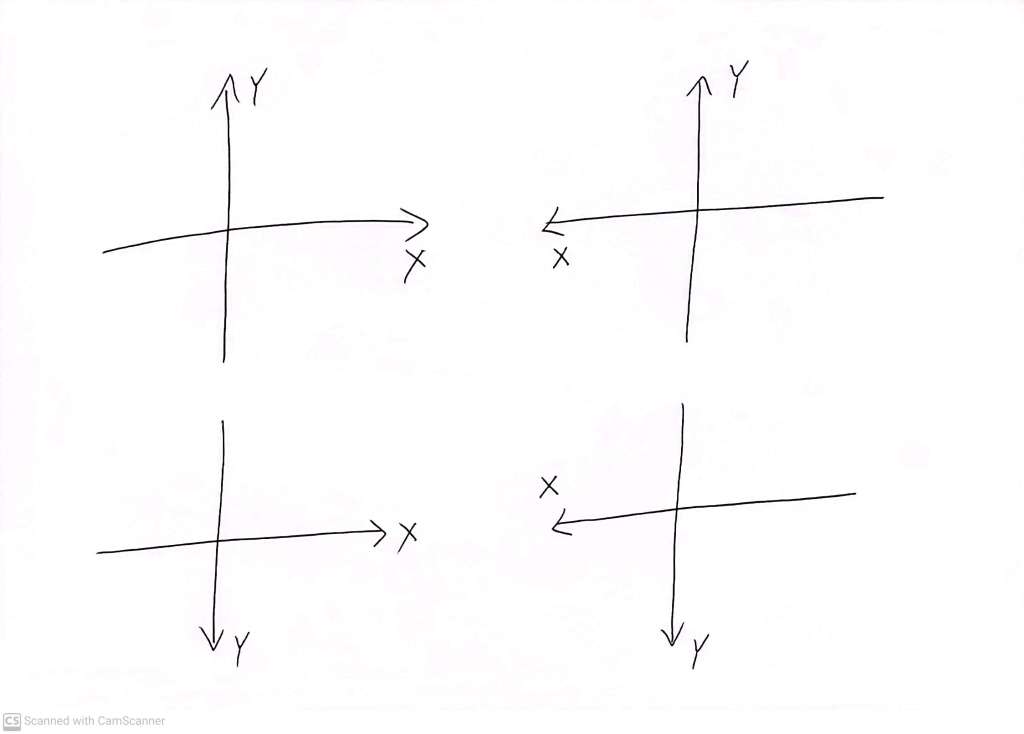

The following are all equally valid:

But it takes (most of us) a bit more effort to keep track of what’s going on in coordinate systems with these alternative labellings because we become accustomed to the usual labelling.

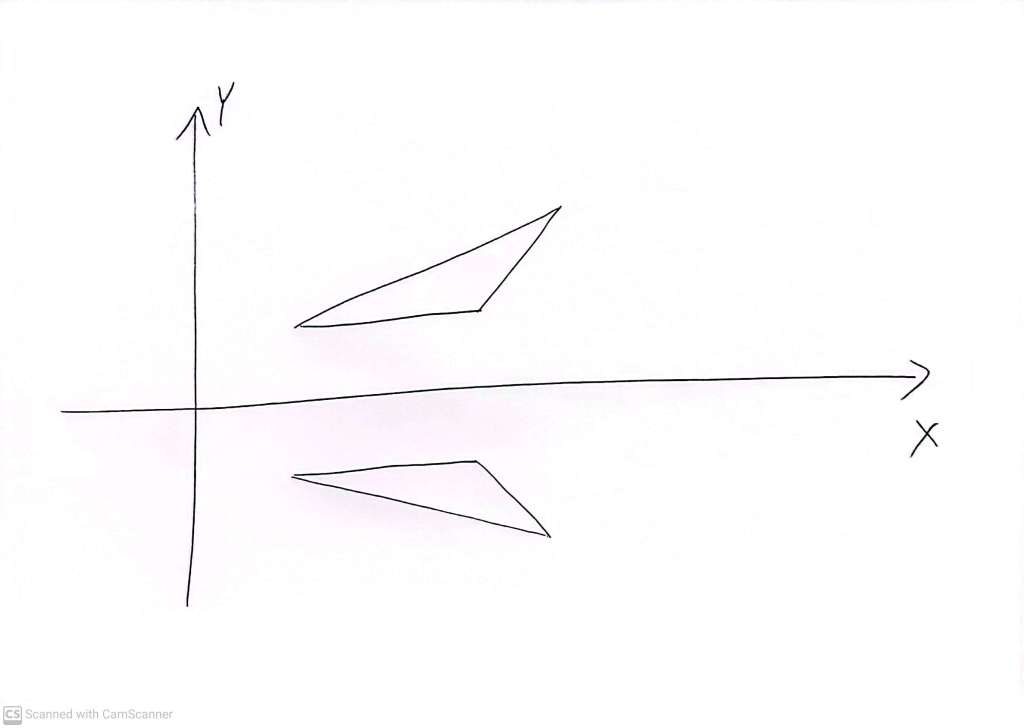

In part one of this discussion, we looked at reflections of a triangle whose sides are all of different length. This is sometimes called a ‘scalene’ triangle – which just means that it is neither ‘equilateral’ (all three sides equal) nor ‘isosceles’ (two sides equal to each other, and the third side some other length). Here is a scalene triangle at its reflection, with the mirror line being the X axis

Our way of understanding the effect of reflection was to imagine walking around the perimeter of the two triangles and noting in which order one encounters the three sides of different lengths. For this to be meaningful, we have to be very clear about whether the triangle we drew was the view of the triangle from ‘above’ or ‘below’, so that we can clearly decide how the walking is taking place. We also have to specify whether the walking is taking place with the interior of the triangle on the left or the right of the walker. If these details of the walking are clearly spelled out, and if they are set up to be the same for the two triangles, then we encounter the three sides in a different order on the original triangle versus the reflected triangle. For the three sides of a triangle, there are only two ‘truly different’ orderings of the sides. After you start walking on the shortest side, you either

- first reach the longest side, and finally the mid length side, as in the upper triangle in the picture above, or

- you first reach the middle length side, and then the longest side, as in the lower triangle in the picture above.

There are no other possibilities. So called ‘congruent’ triangles are pairs of triangles with the same lengths for their three sides – irrespective of the ‘order’ in which they are ‘strung together’.

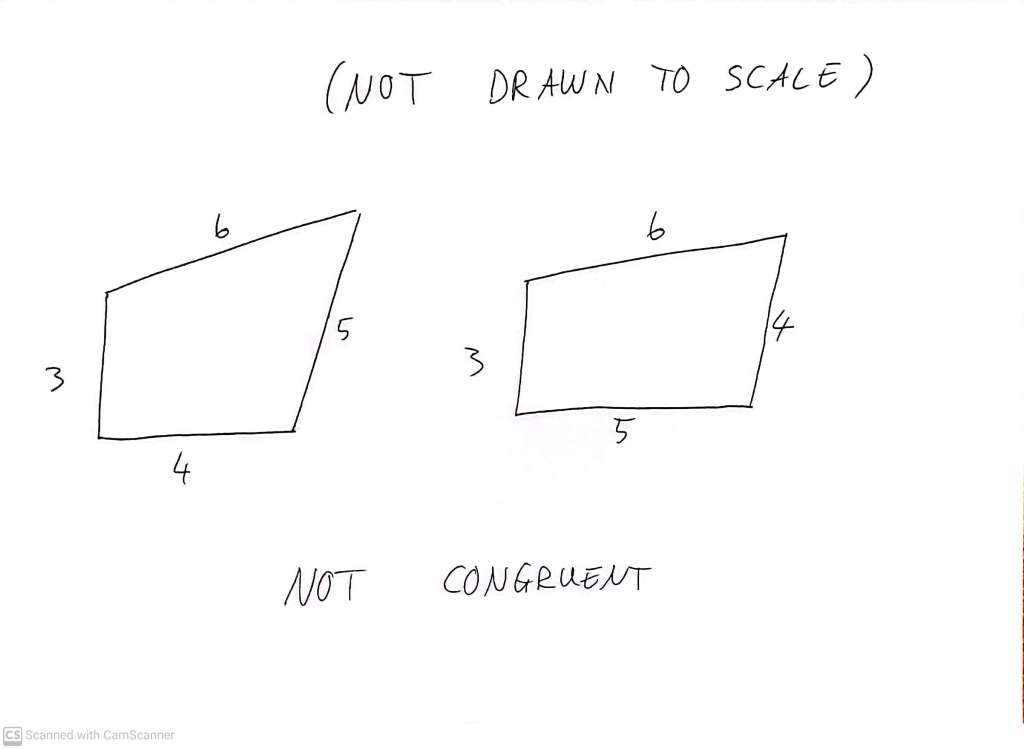

For shapes with more than three sides – let’s say four (quadrilaterals) – it gets more complicated. If I say quadrilateral-A and quadrilateral-B have the same side lengths – for example 3,4,5 and 6 metres – then it does not necessarily follow that they re congruent to each other. I can potentially (it depends on the lengths of the sides) string the sides together in fundamentally different ways, to generate shapes that are not even congruent, even though the four lengths of the four sides are the same

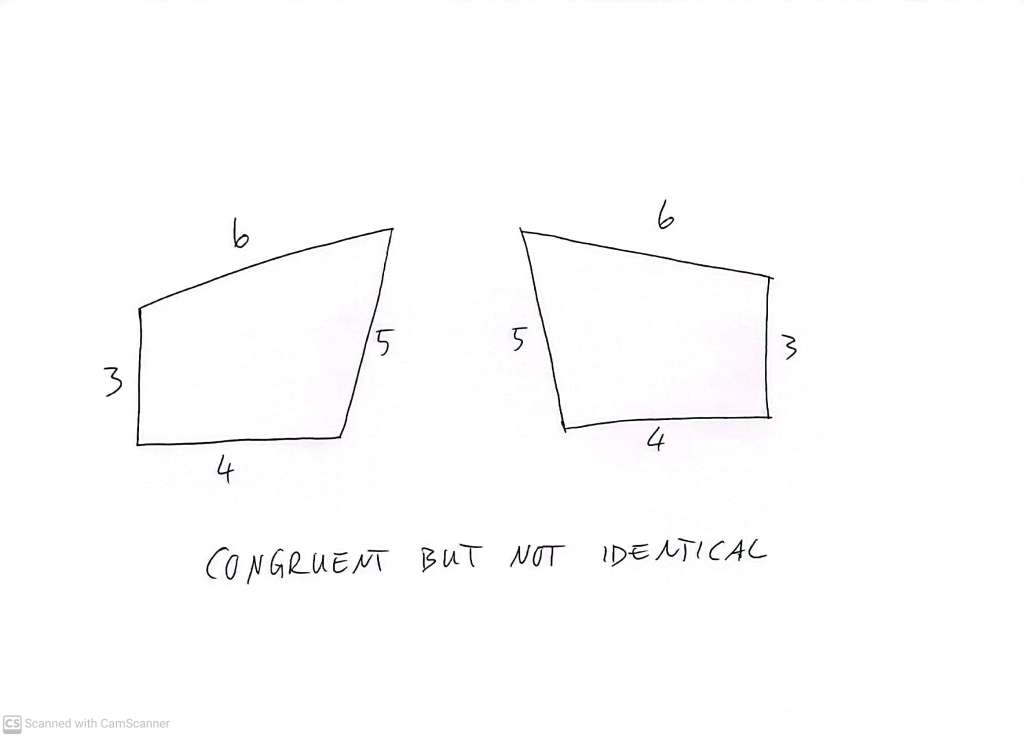

But of course there are also always ways of making congruent quadrilaterals which are not fully equal – and which become each other under reflection

The reason we’ve gone into such detail is ultimately to be able to see how, and whether, various labellings of the X and Y axes really differ from each other.

On the face of it, for each of two axes (the X and Y axes), we have two, nominally independent, choices for which direction of the axis is the positive direction. That’s how we produced 4 superficially different diagrams. Looking more closely, we can see that we have two copies of each of two situations. One version of the XY coordinate system has the positive Y axis a quarter turn clockwise from the positive X axis

and one version of the XY coordinate system has the positive Y axis a quarter turn anti-clockwise from the positive X axis

There are clearly no other possibilities.

Defining directions in three dimensions

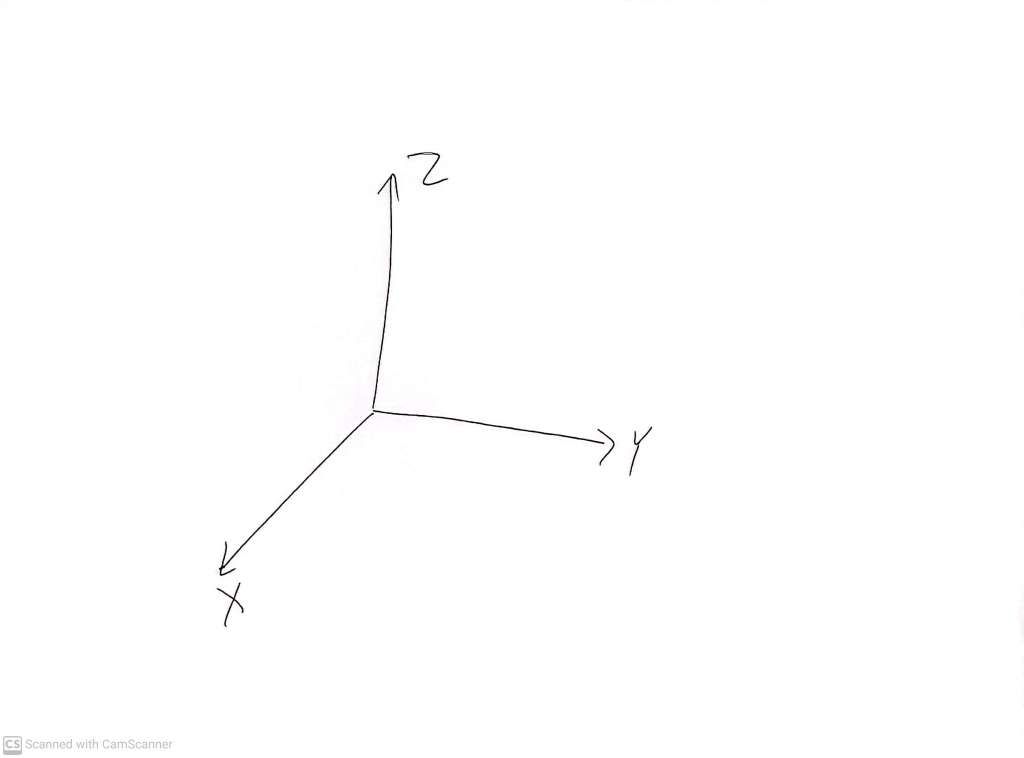

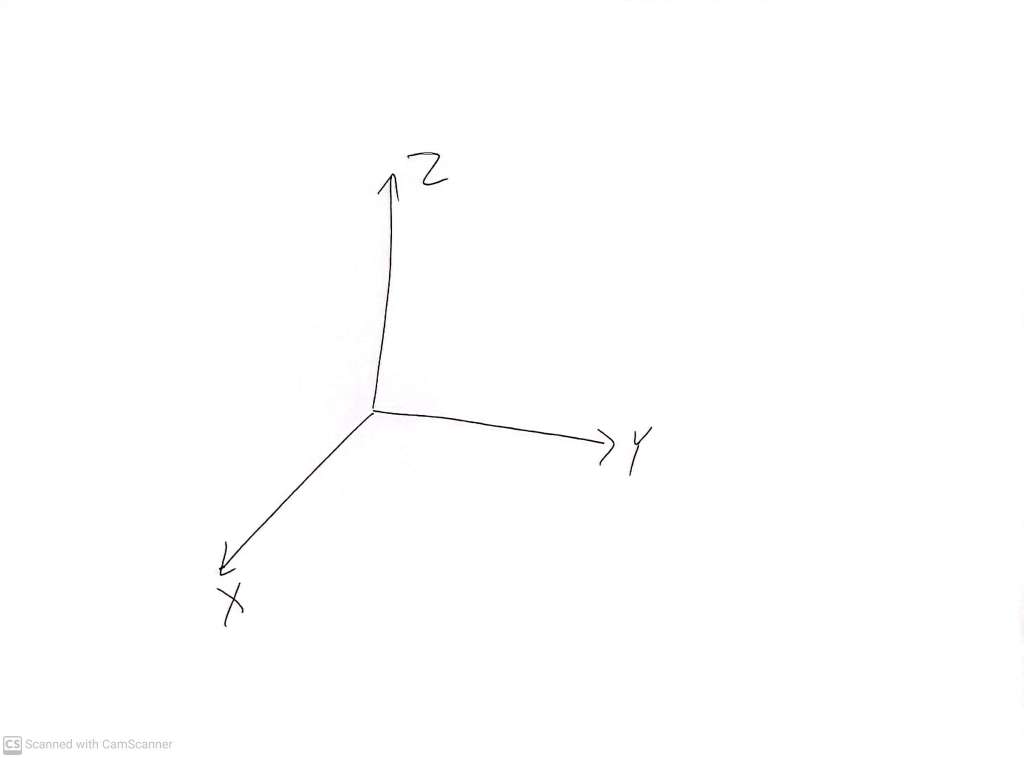

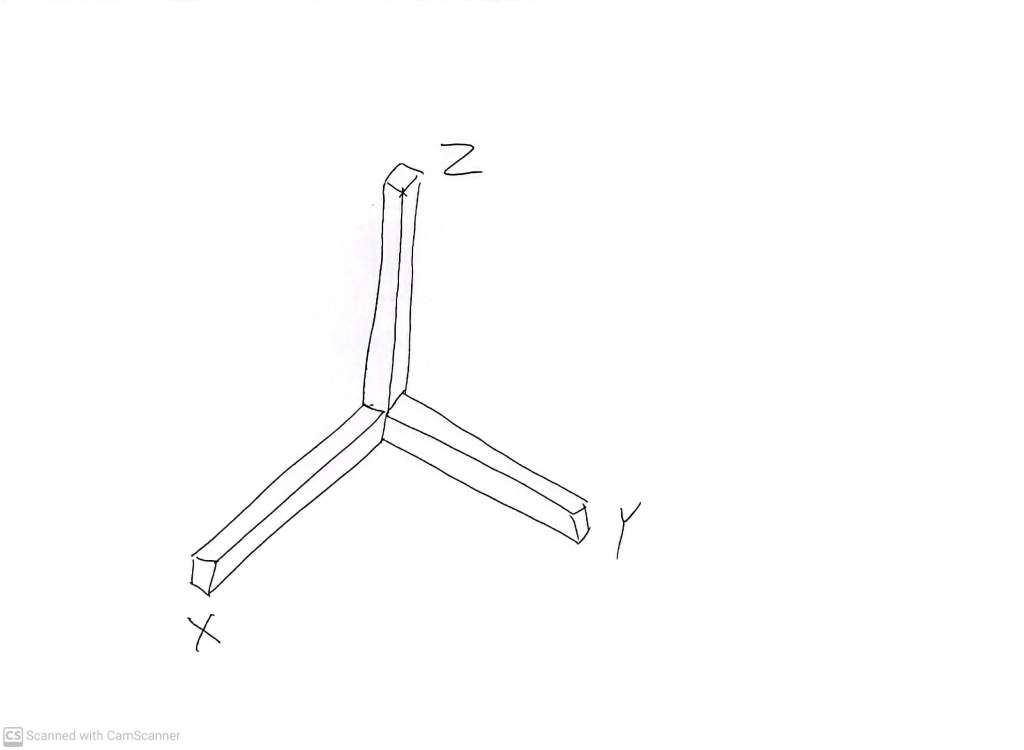

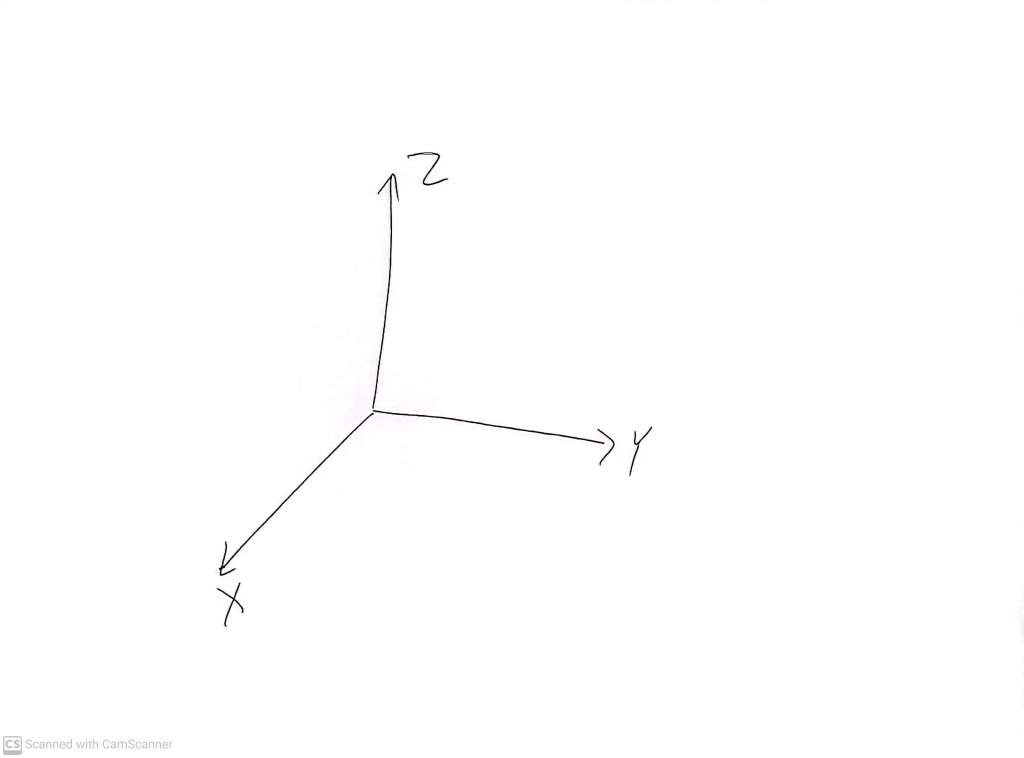

In three dimensions, the conventions are not quite as strong, but it is very common to see something like this:

Which is usually understood to mean that the X and Y coordinates label a ‘horizontal’ cartesian plane, such as the floor of a room, and a positive valued Z coordinate indicates ‘height’ above the XY plane (floor). Again, this is just a convention. These coordinates have no meaning other than what we give them. But drawings like this are not always clear.

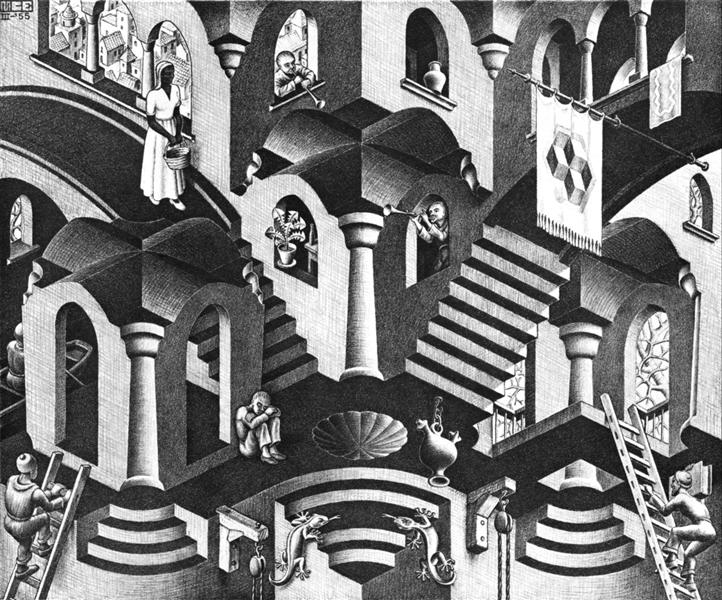

Three doesn’t really go into two

Squashing three-dimensional objects onto a two-dimensional page risks ambiguity, and we don’t want to clutter all our diagrams with doors, windows, and carpets. You have probably seen images like the paintings of MC Escher. This one is known as ‘concave and convex’.

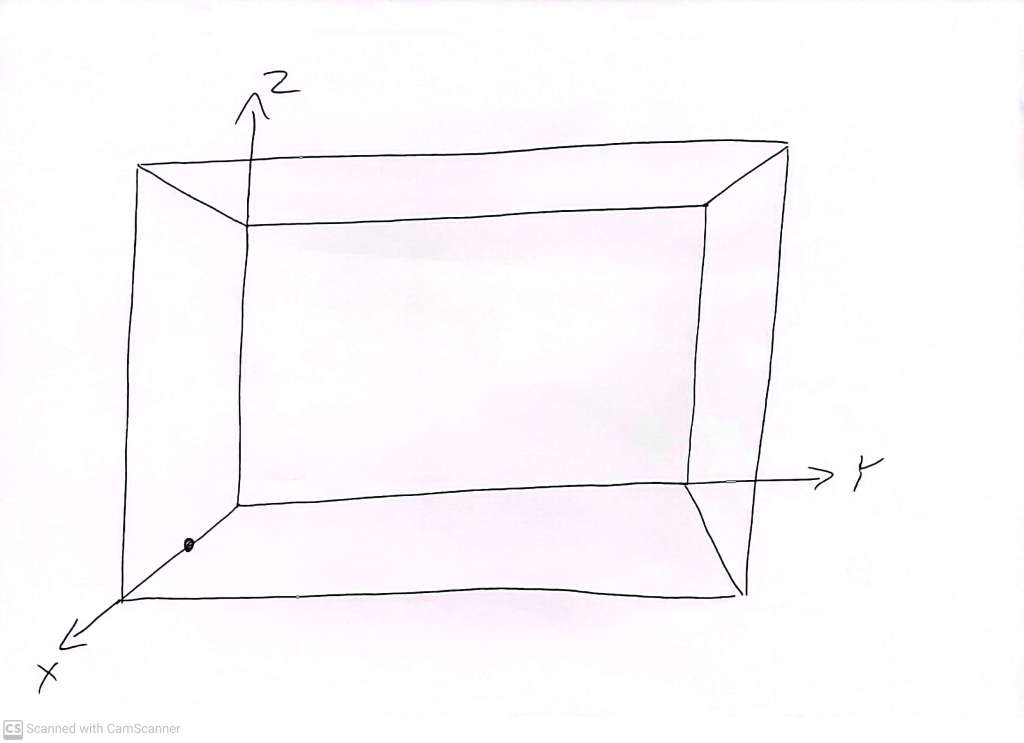

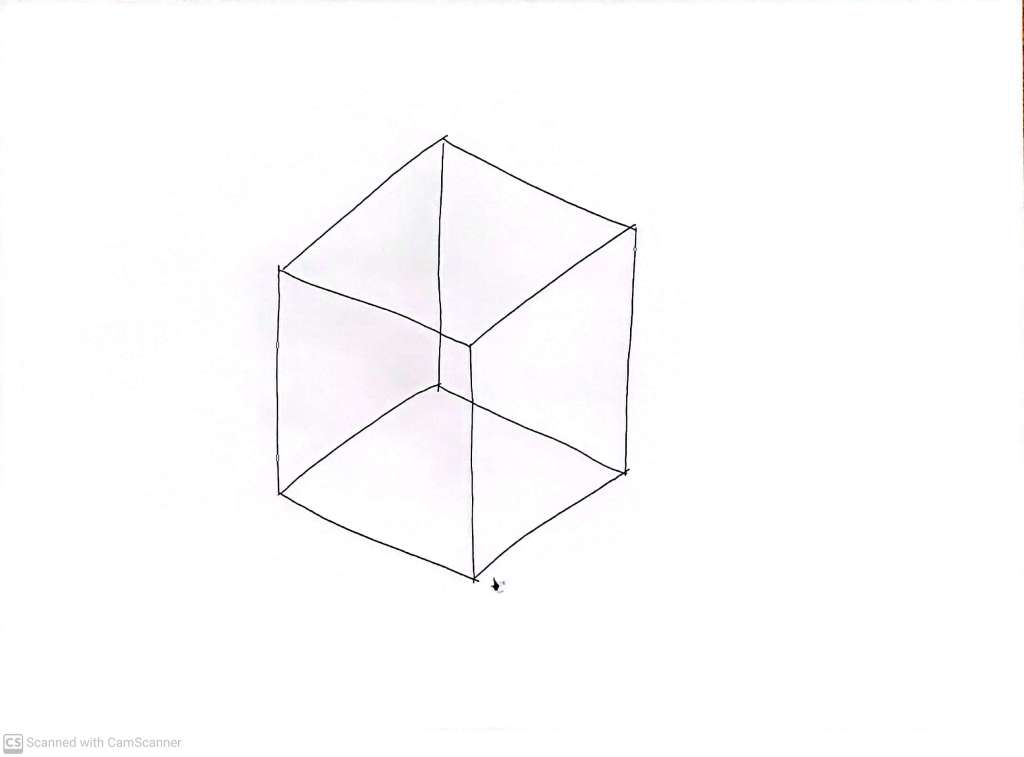

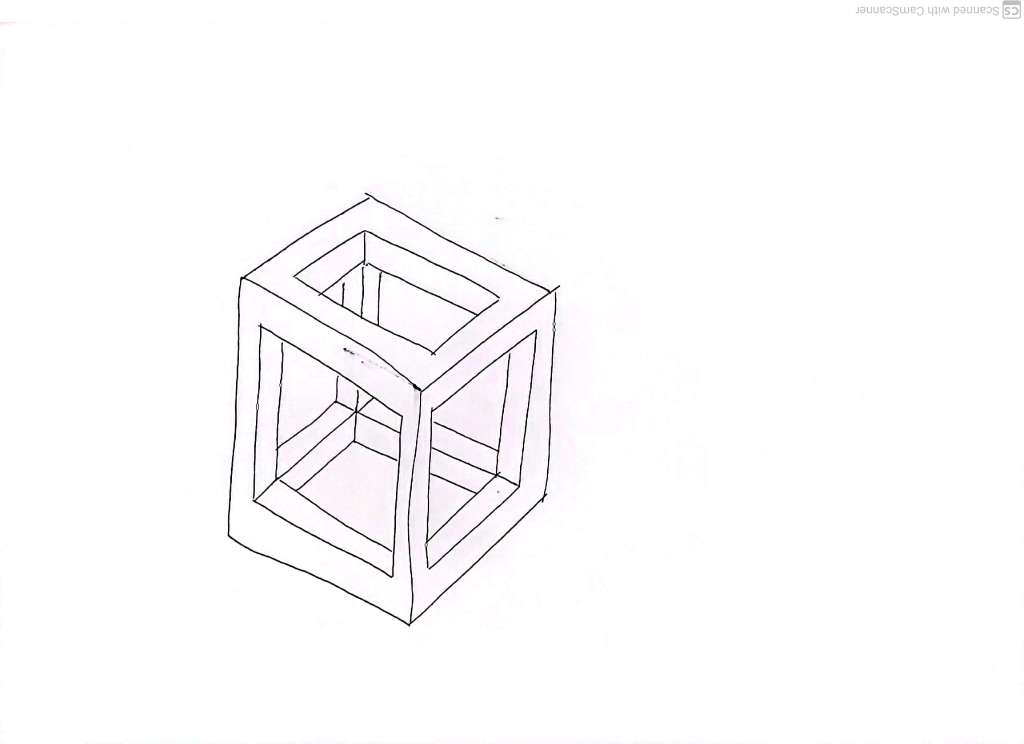

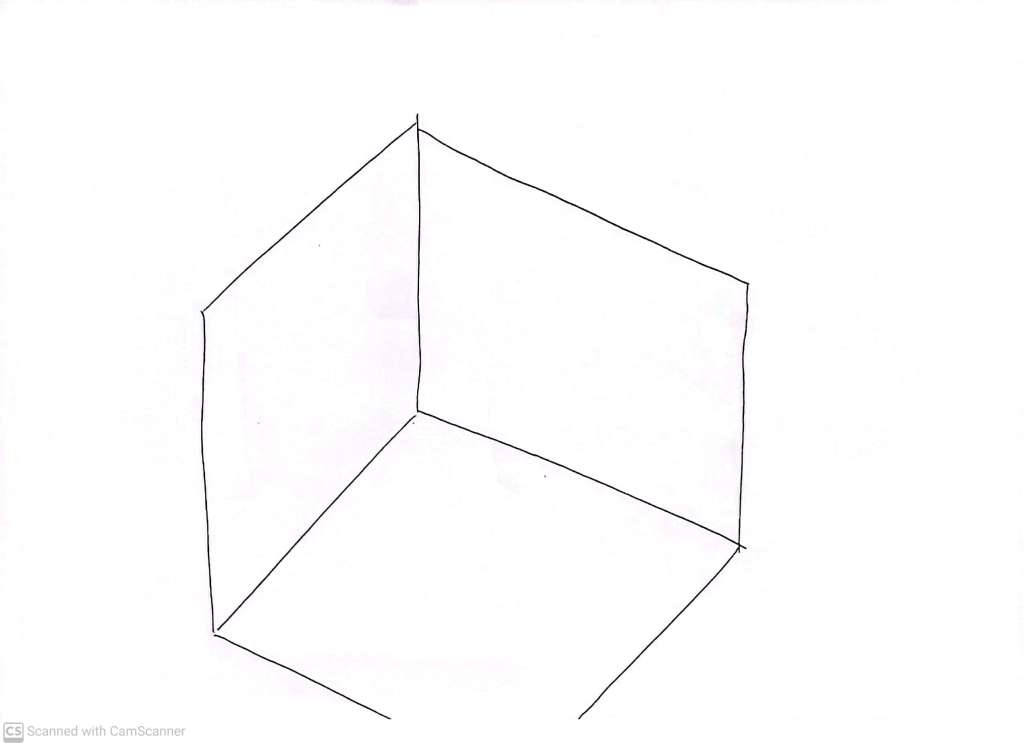

So we have to be very careful about what we are drawing. If we just draw this image of a cubical wire frame

then it’s not clear from which angle we are viewing it. If we add a bit more structure, like this:

It becomes pretty clear what we mean. Alternatively:

To make sure we know what we mean when we draw this

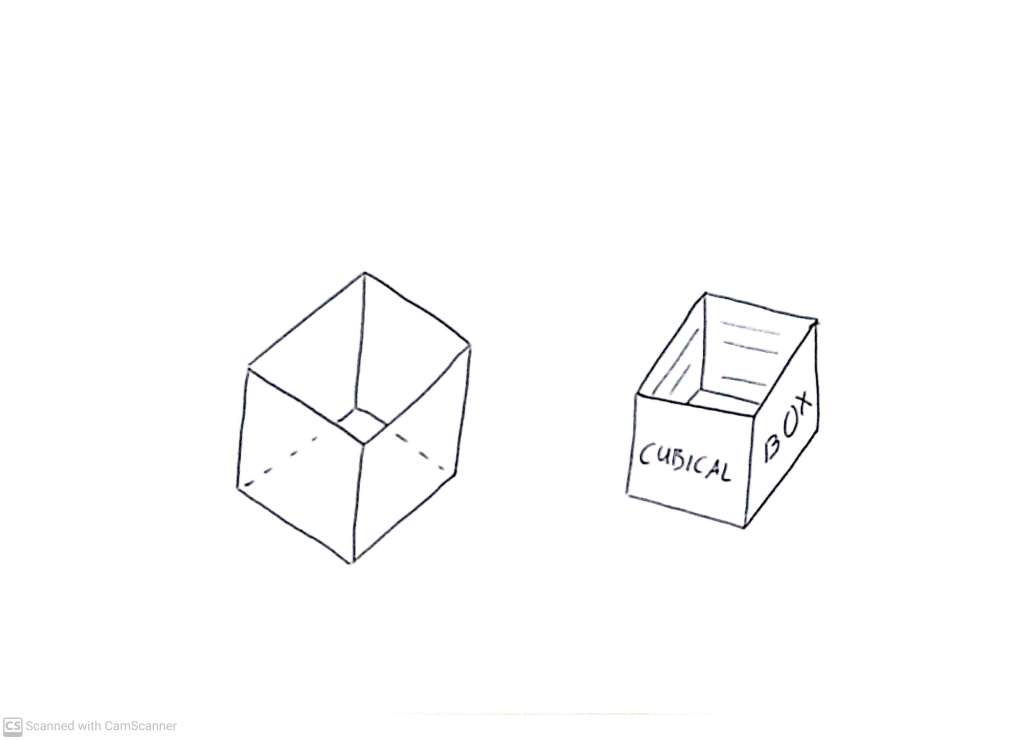

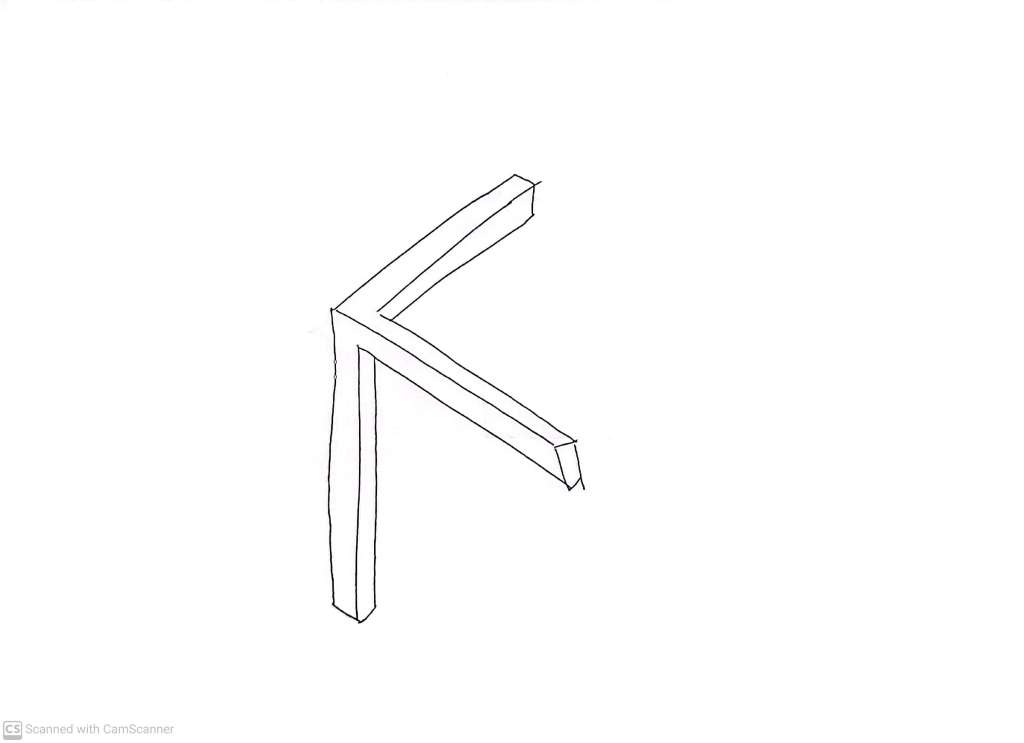

We can think about a lidless cubical box on a table.

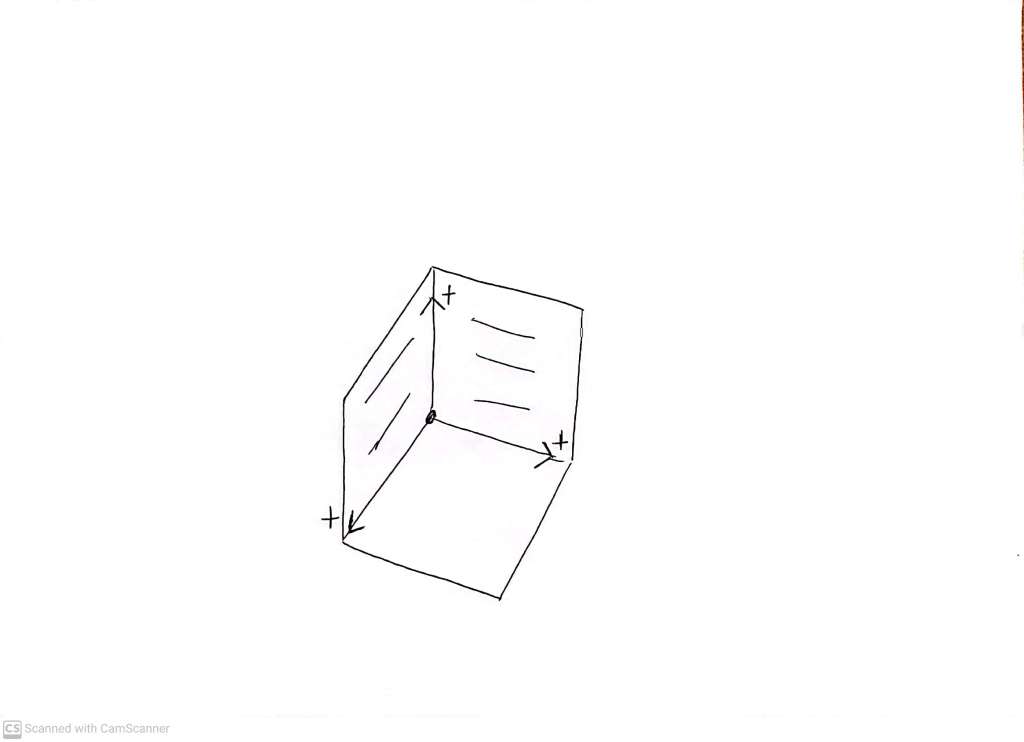

We can break off the two vertical sides closest to us, and treat the remaining three-sided object as a support for our coordinate system.

The point where the three remaining sides (‘faces’) of the box meet (a point known as a vertex) will be the origin of the coordinate system. The creases between pairs of ‘faces’, which are known as ‘edges’, will serve as the *positive* sides of our axes. I call this the ‘concave’ (hollow, caved in from the point of view of the viewer) interpretation of these pictures

Alternatively, imagine looking up at a crate being hoisted by a crane

The three visible sides/faces, and three visible edges, of this cube make for essentially the same arrangement of lines as the concave remnant of the box, but this is a ‘convex’ interpretation of the picture.

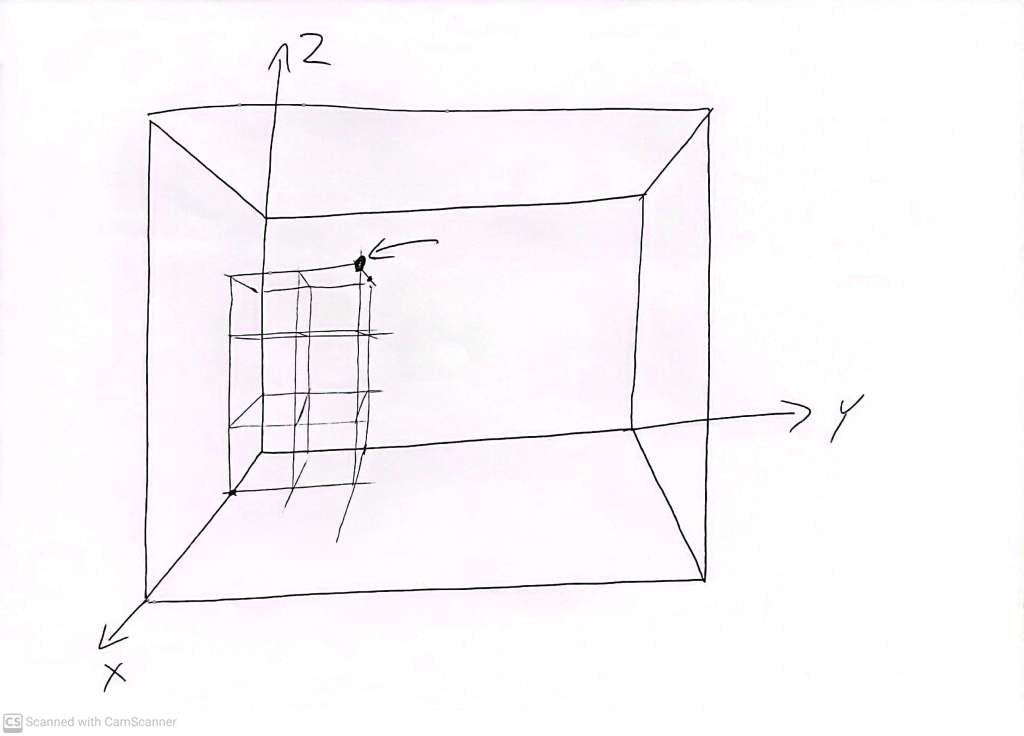

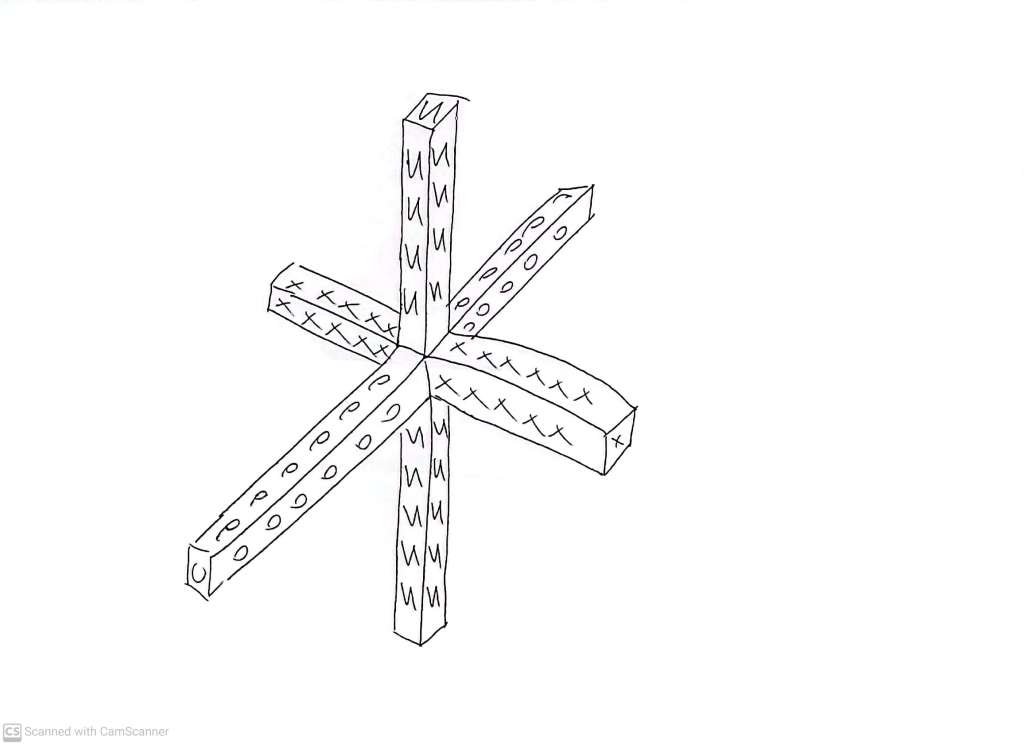

Now imagine we have chosen three mutually perpendicular (‘orthogonal’, in fancy mathematical language) axes

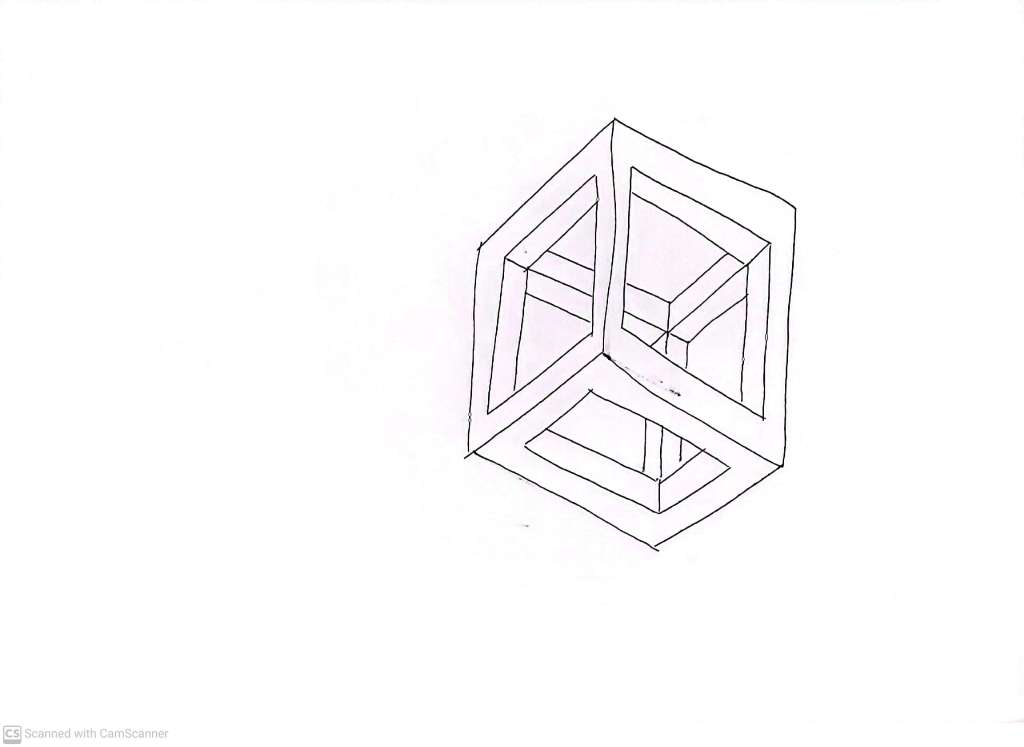

If label one side of each axis as the positive side (deferring the decision of which one is X, Y and Z), then we cannot avoid labelling a set of three which can be seen as three edges of a cube which meet at a vertex, such as

or

Once we have chosen the three positive axes, we can always reorient the coordinate system so that the three positive arms are aligned with the three edges of the stripped down box as it stands on the table.

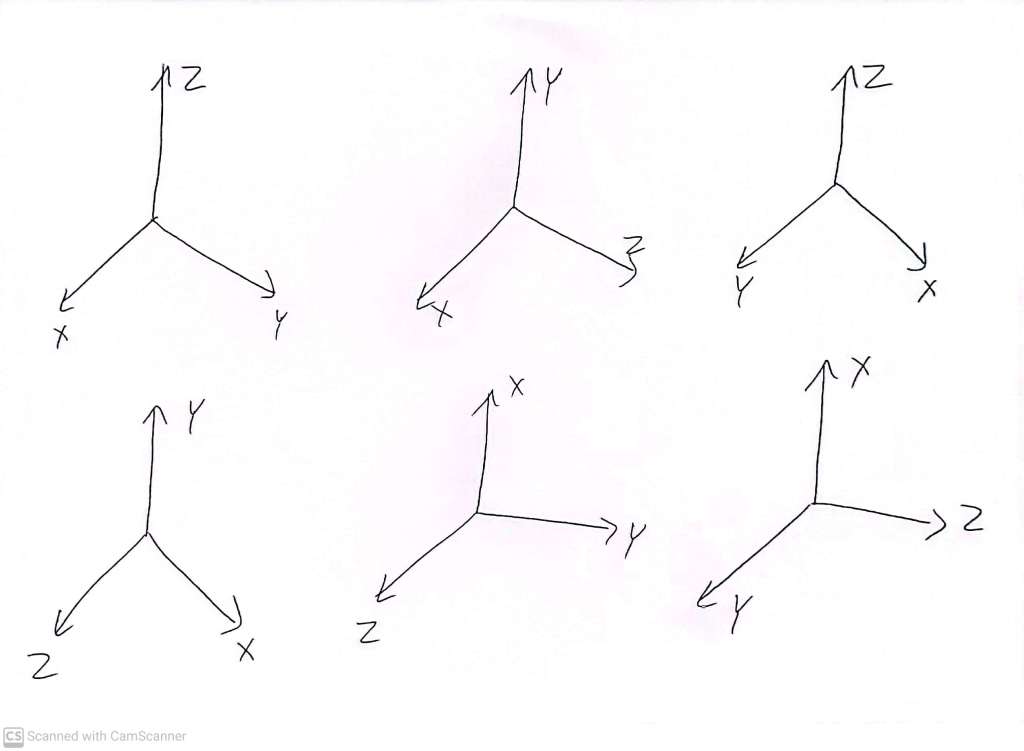

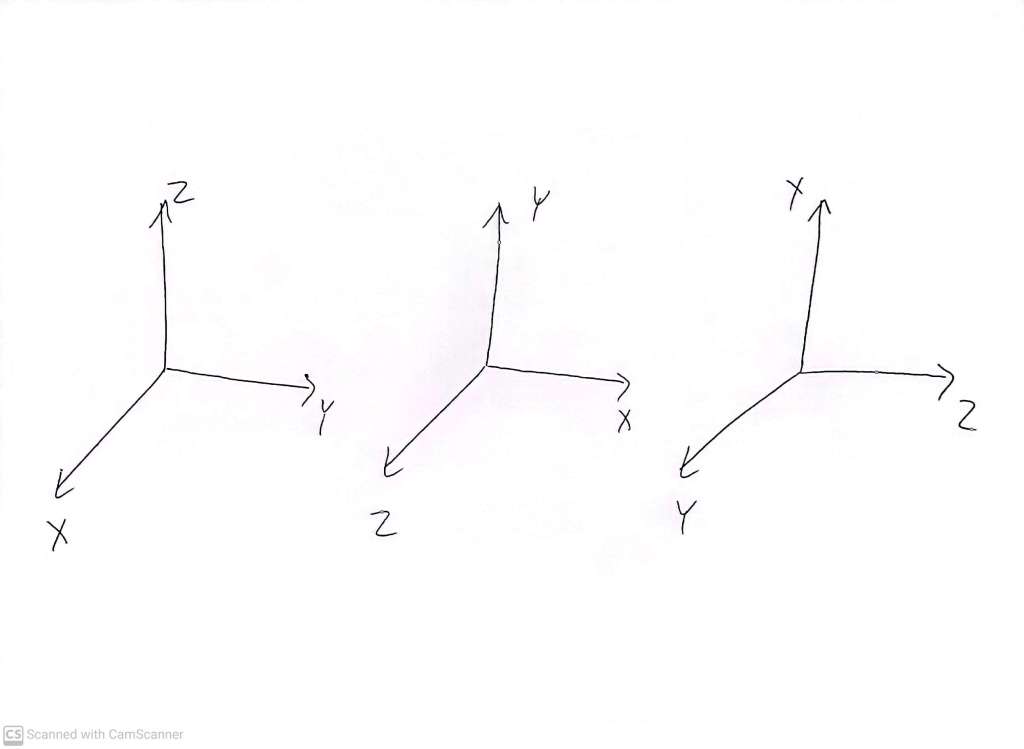

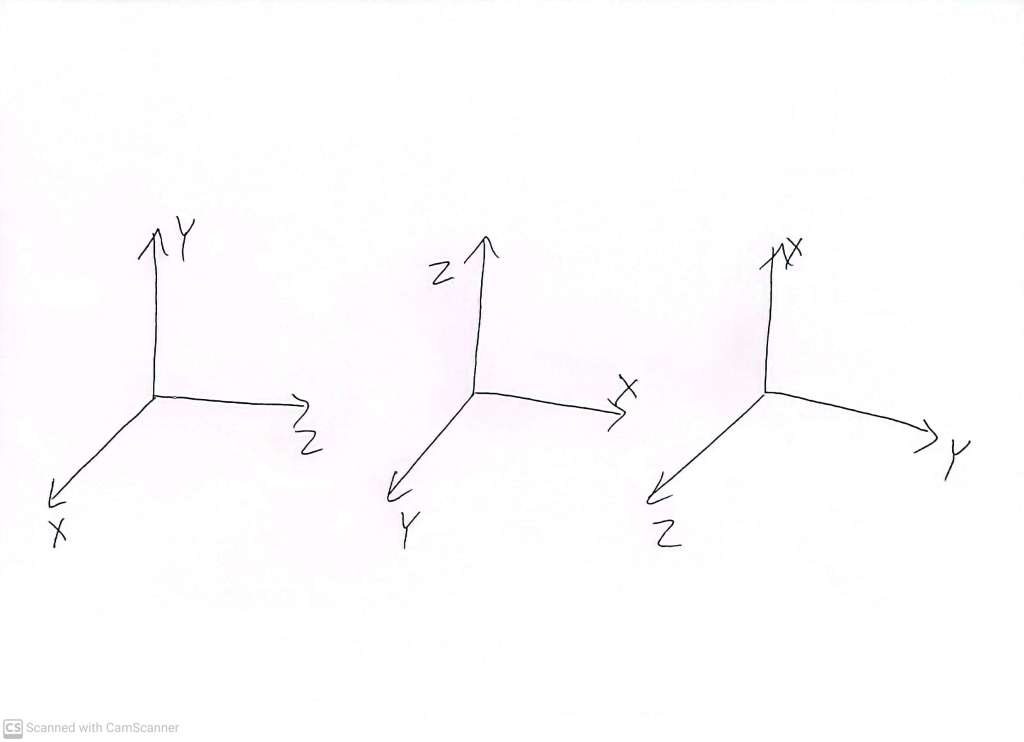

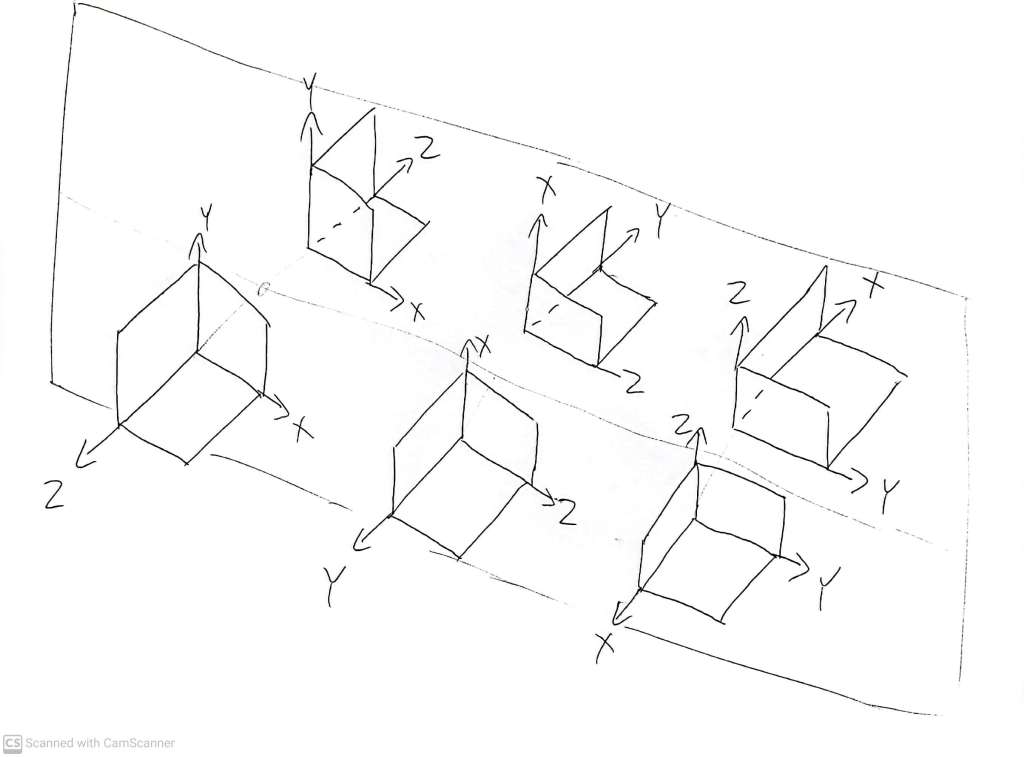

In order to understand the possible ways to construct a cubical coordinate system, we need only think about how to distribute the X, Y and Z labels to these three positive axes. We can add the labels X, Y and Z in what might appear to be 6 different ways:

But really there are ‘intrinsically’ only two meaningfully different ways.

These three are essentially the same as each other

And these are the other three, which are the same as each other.

Within each set of three that I call ‘the same as each other’, we can ‘rotate’ (hold in our hands, twist around in some way, and put back down, if we want) any one into any other. We can’t rotate any one from the one set of three into any one of the other set of three. Remember that we are talking about the concave interpretation of the axes, and that the axes are rigid and we are not allowed to bend them in any way. There is no third fundamentally different way of labelling three axes in three dimensions. So, however we choose and label three orthogonal directions to serve as a three dimensional coordinate system, we ultimately create one or other of these two scenarios. And yes, you guessed it, these are often referred to as left handed and right handed versions or a three dimensional (so called ‘Euclidean’) coordinate system.

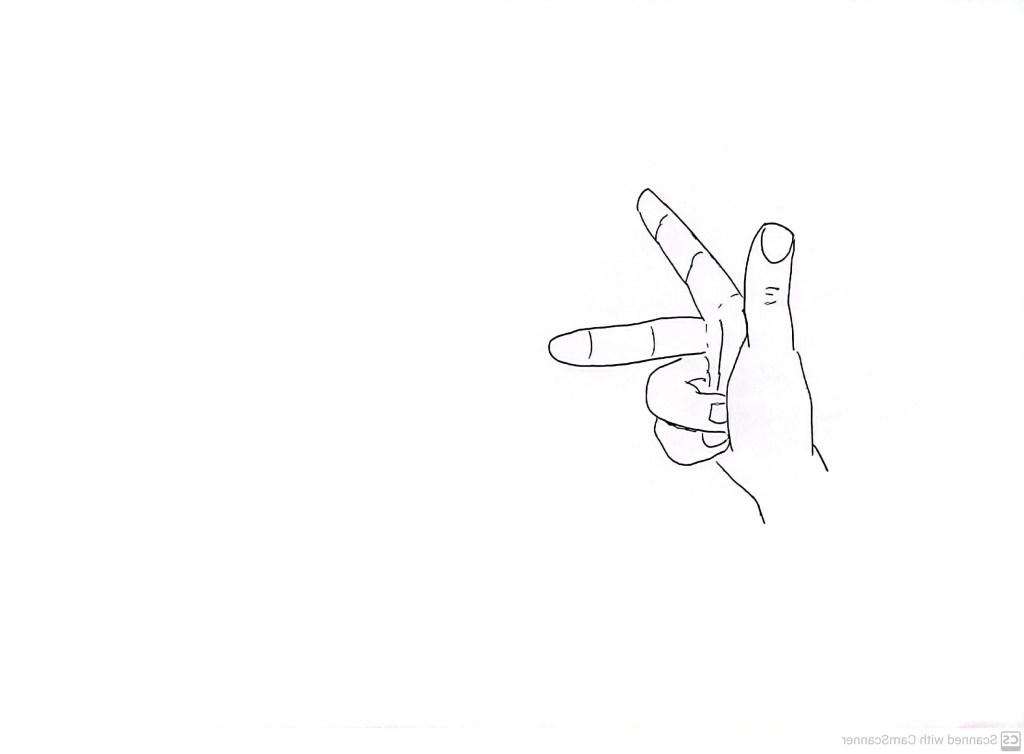

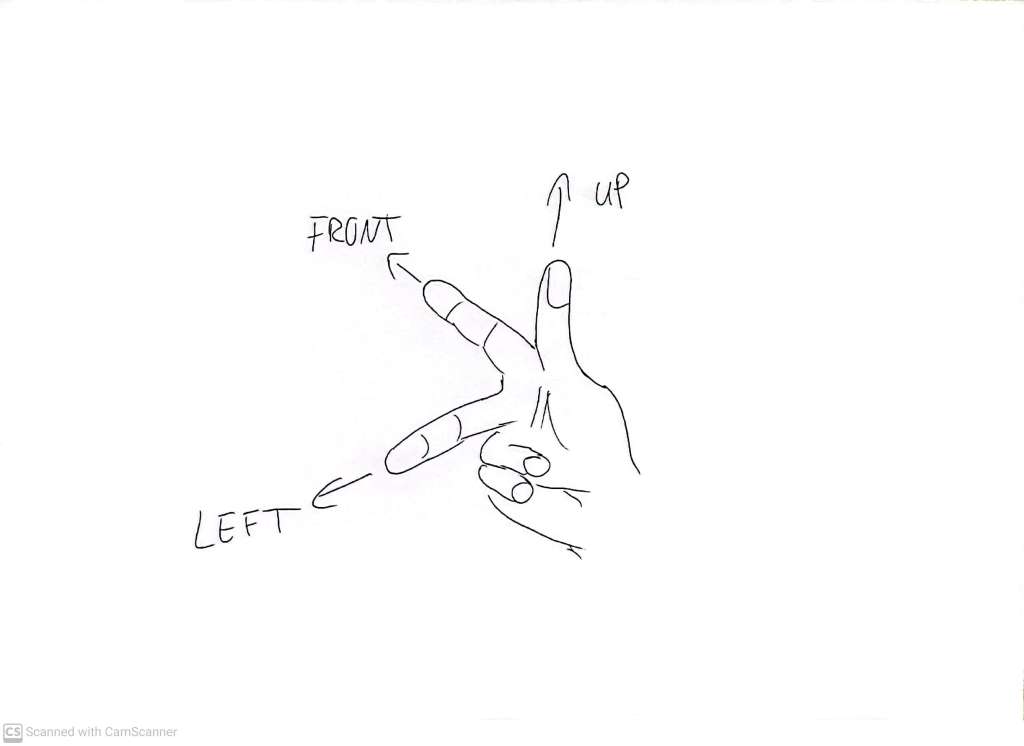

It doesn’t really matter which one we call left handed and which one we call right handed, but it makes sense to use a human hand as a reference tool. Hold your RIGHT hand with your thumb flexed ‘up’, your index finger in its classical ‘pointing’ pose (making a right angle between the two), and point your middle finger so that it is perpendicular to both your thumb and your index finger, like so:

Now we label the fingers, starting with the thumb (X), then the index finger (Y) and then the middle finger (Z). Although the overall orientation is different, this is equivalent to our coventional

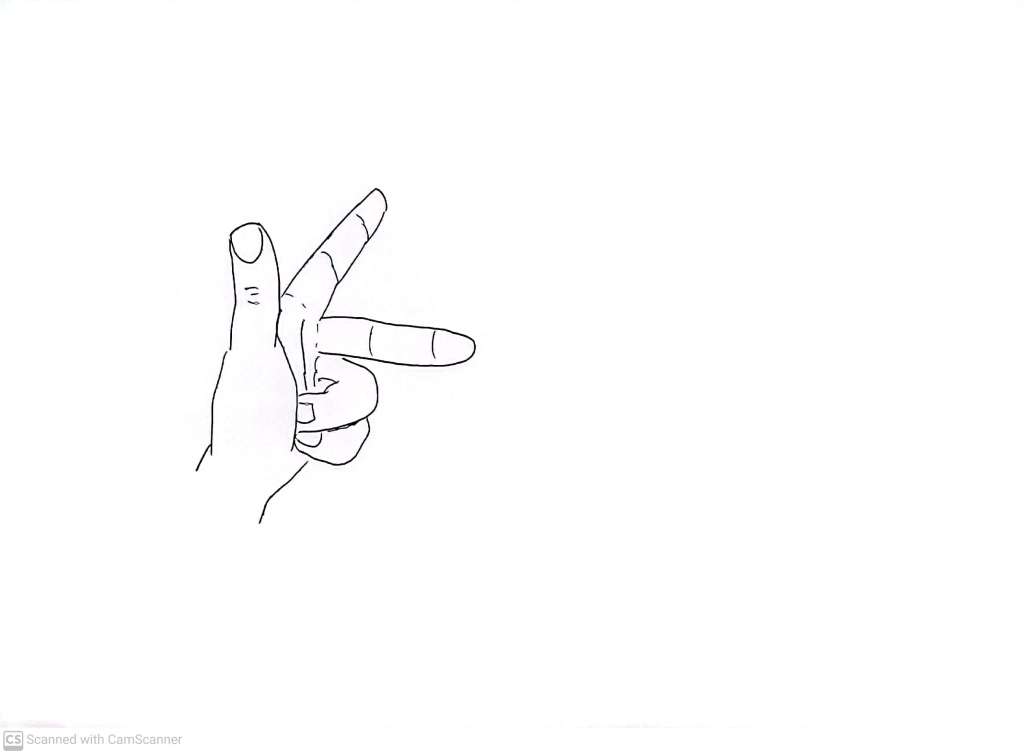

It’s worth trying to hold your right hand in our three prong gesture, with your thumb pointing towards you, the index finger pointing right, and the middle finger pointing up – jut to convince yourself. We can also hold our left hand in the same way we just used the right hand.

And again label the thumb X, the index finger Y and the middle finger Z. This corresponds to the other version of the XYZ coordinate system.

Left and right defined, at last

Often, we think of left and right as labels for directions. This could make sense even if we were robots with two identical hands. As it turns out, our left hands are mirror images of our right hands – congruent but not identical – and so left and right have also come to be used as labels for versions of shapes which differ just by a reflection.

An old joke my parents sometimes made, nominally for remarking to people who have mixed up left and right, is to ‘remind’ them that the left hand is the one where the thumb is on the right, and the right hand is the one where the thumb is on the left. Presumably the intended point of the joke is that it really is all very arbitrary and you can’t really explain left and right in words, but if you’ve made it this far, you may be thinking that the remark implies some not fully spelled out vantage point – for example one which sees the back, not the palm of the hand, and has the fingers pointing away from, not towards, the observer. Such is the nature of the detail we need to grapple with (with both hands) to get to the bottom of the handedness conundrum.

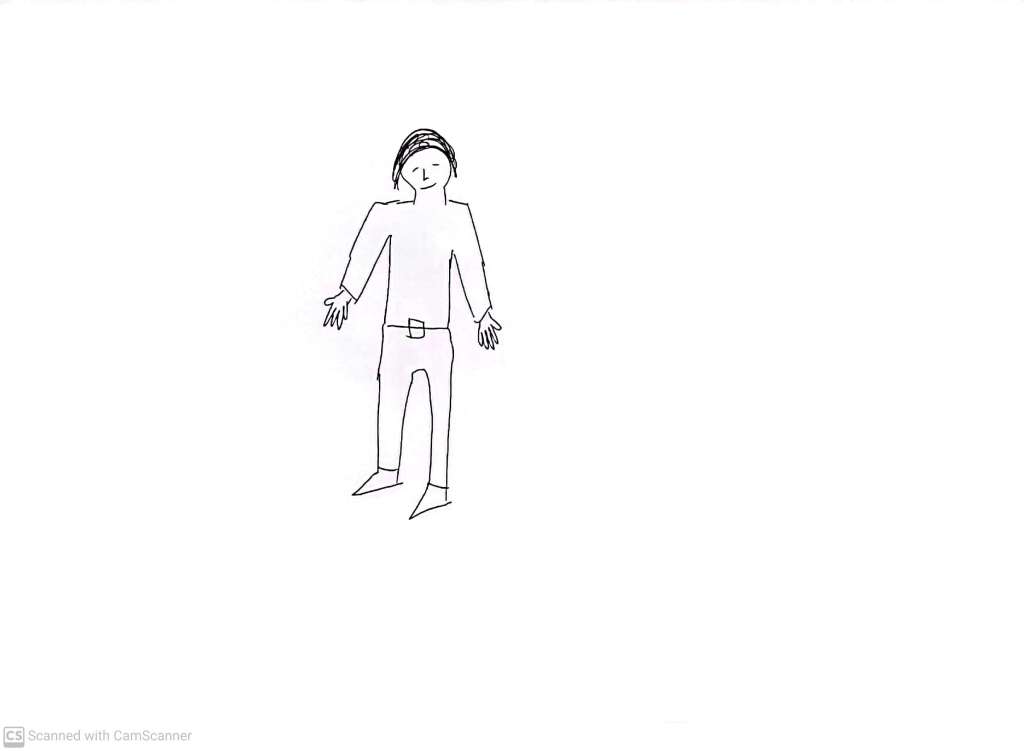

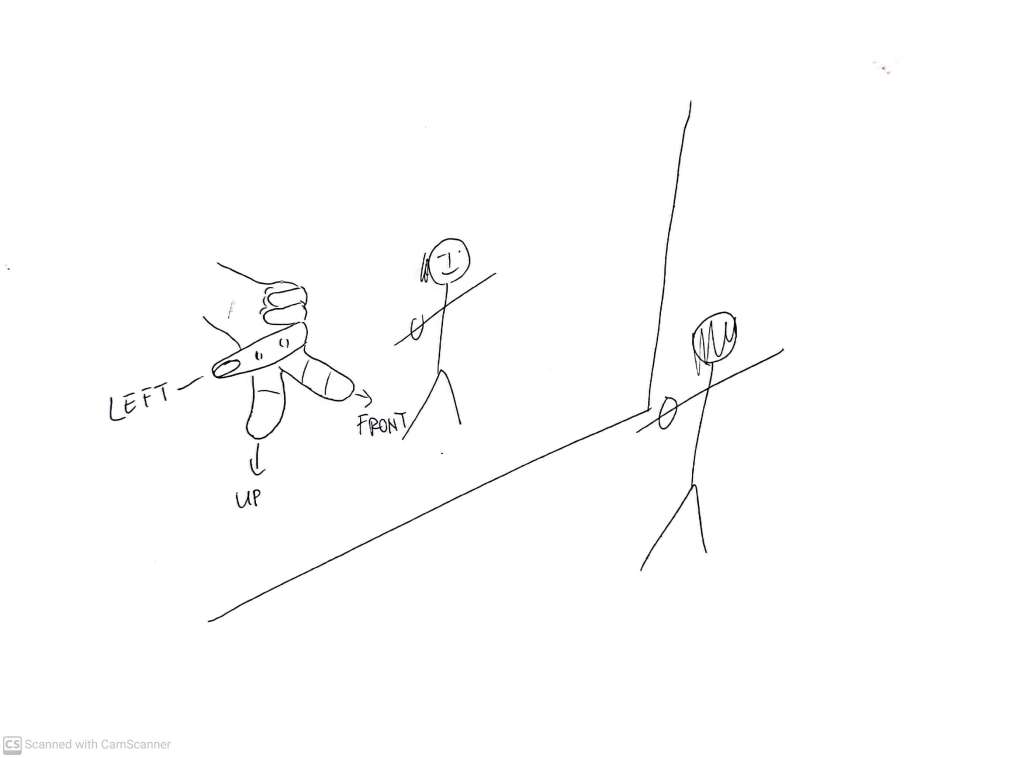

So, agreeing that people look roughly like this:

We can pull one aside, and declare 1) that the face is on the front of the head, 2) that the head is at the top, and 3) (grabbing an arm and putting a watch on the wrist) that the watch is on the left hand. This recipe depends crucially on constructing, or at least referring to, an object which demonstrates an arbitrary definition – in this case, a watch-wearing person.

Notice that left and right only have meaning in relation to both UP AND FORWARD, or both DOWN AND BACK, or whichever way you want to create the two other reference directions. Interestingly, then, left and right actually have no stable meaning in a 2 dimensional coordinate system! Life in 2 dimensions is even weirder than we usually imagine, a small detail usually not emphasized in stories from ‘flatland’.

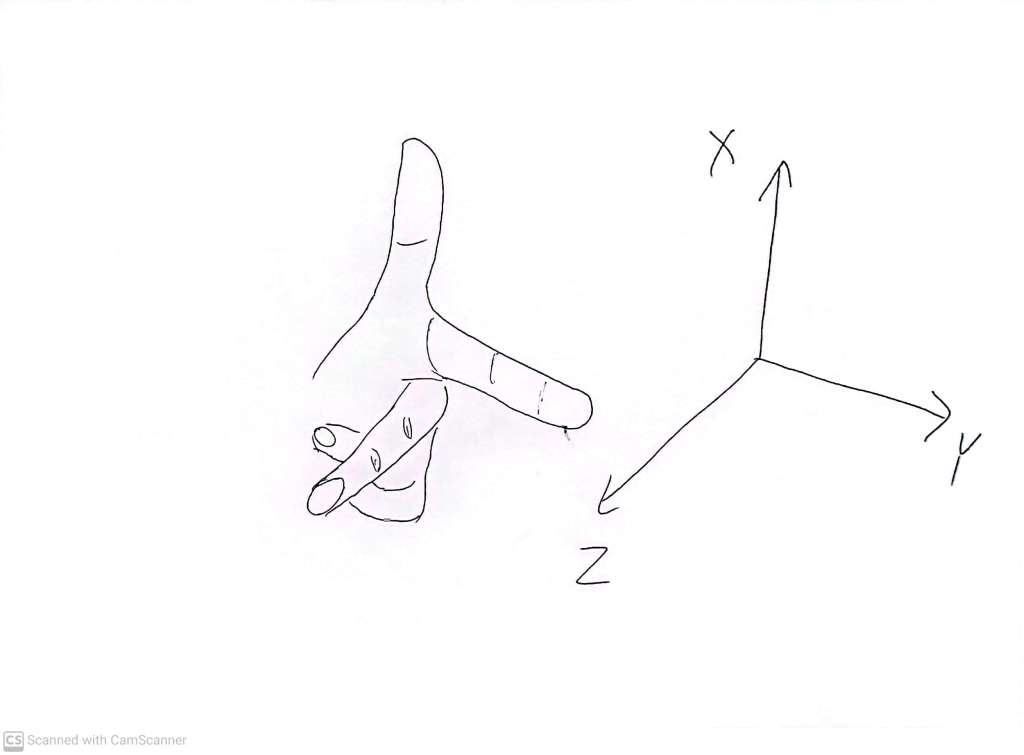

In order to have a symbolic presentation of Up, Forward, and Left, which is less loaded than a whole person, notice that the hand gesture of earlier can be used by labelling the thumb as up, the index finger as forward, and the middle finger as left.

Through the looking glass, at last

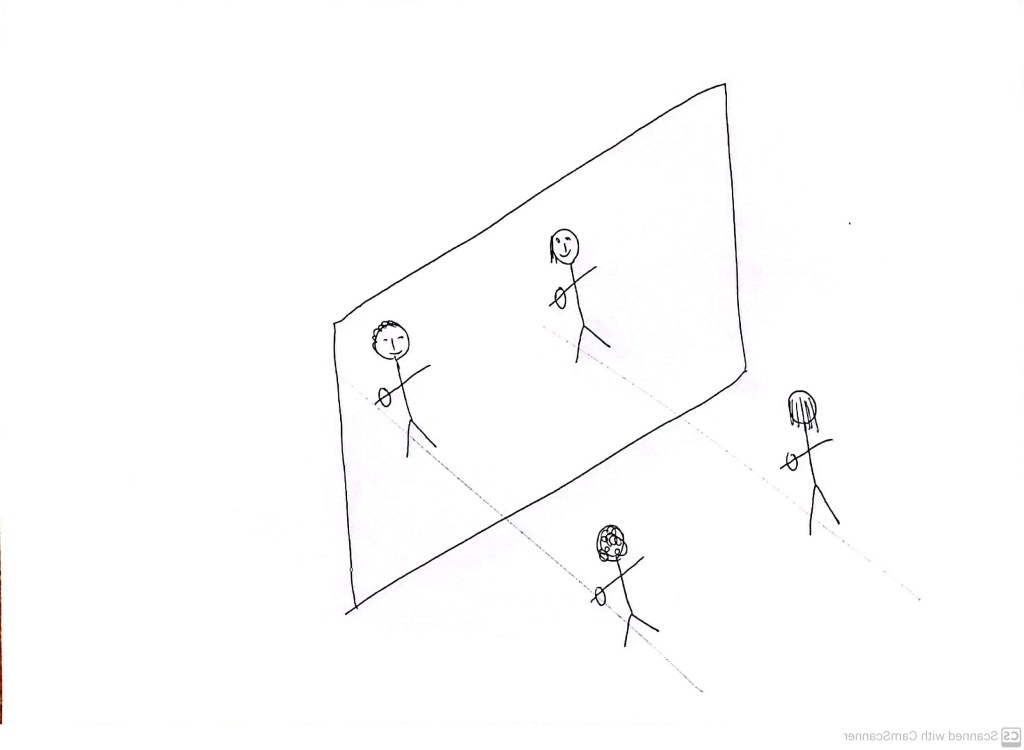

Imagine two people facing a mirror, in a realm where, like at the beginning of this chapter, we can see both the ‘real’ and ‘reflected’ rooms as co-existing.

At this stage, we have learned that, in order to decide whether the watch in the mirror is on the left or the right hand, we have to be clear where up and front are. Perhaps the curly haired person walks into the mirror room (their reflection disappears, of course):

They are likely to conclude that the watch of the reflected straight haired person is on their right hand. It is very easy to fail to explicitly observe that we have just quietly assumed that the head of the mirror person is at the top, and the face of the mirror person is at the front.

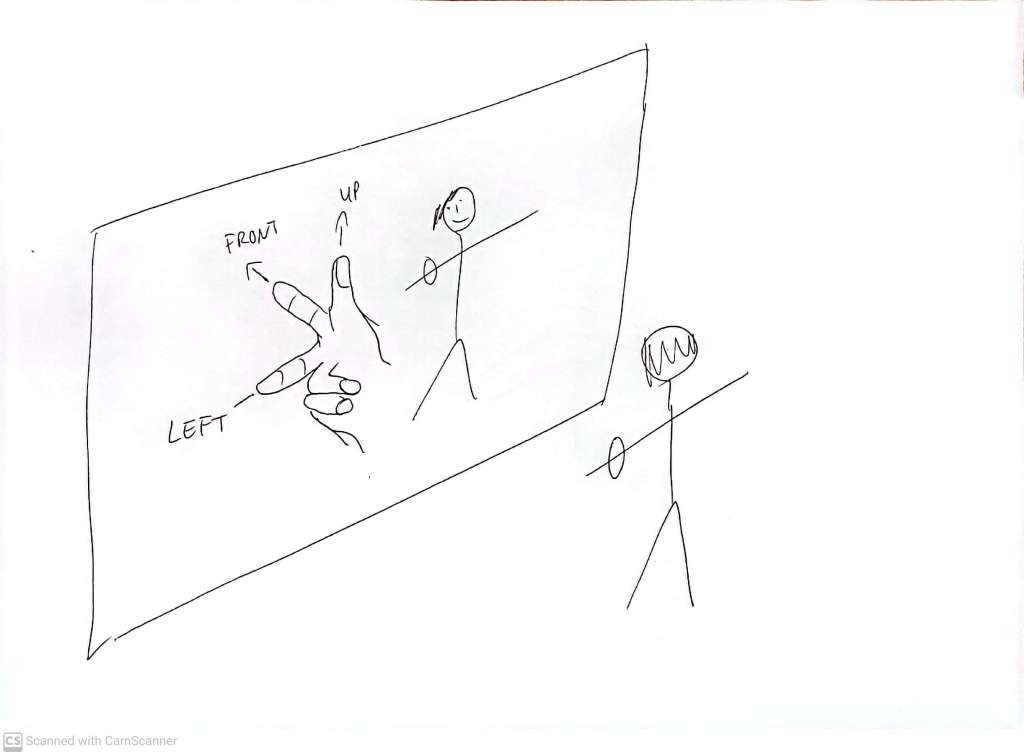

But what if we feel that the crux of our earlier definition is that the watch MUST be on the left hand? Let’s use our right hand direction-gesture to see what this means

Apparently, the face of the reflection of the straight haired person is on the back of the head. If we insist that the watch is on the left wrist and the face is on the front of the head:

then the head is at the bottom and the feet are on top – and yes, that is a right hand.

It’s very easy to believe that the head is up and the face is on the front of the head. The other two intepretations just don’t feel natural. We almost can’t resist ‘walking’ into the mirror world as if it shared a floor with ours, and it’s hard to think of a face on the back of the head without squirming a little – so we barely notice that these are arbitrary conventions with no real natural justfication.

Depending on how we hold our standard hand gesture up to a mirror, or, even simpler, the cardboard shell labelled as in the concave interpretation of before:

we can set it up so that

- X and Y are the same in the mirror world and the real world, in which case Z is inverted

- X and Z are the same in the mirror world and the real world, in which case Z is inverted

- Y and Z are the same in the mirror world and the real world, in which case X is inverted

If we use a simple abstract thing like a fragment of a cardboard box, with labels like XYZ, we are not so attached to insisting that any particular directions must be the same in the two worlds. Our ideas about UP and FRONT, however, are powerfully triggered by the image of a person. Really, all that happens, in each case, is that, in the reflection, the direction (axis) perpendicular to the mirror is flipped (inverted). Surprise!

In short, either

- the mirror person wears their watch on their right hand,

- OR their face and toes point backwards,

- OR they’re walking on the ceiling / standing on their head.

The mathematics doesn’t much care – and nor do the photons bouncing off the mirror!

Non-mirrored mirror writing

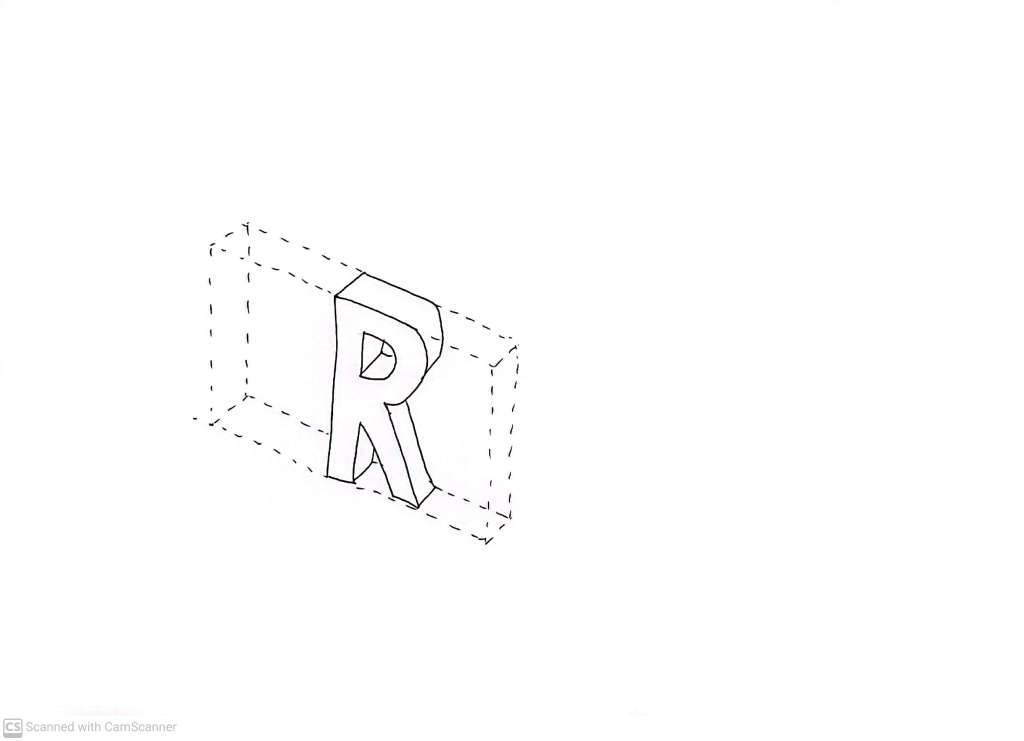

Imagine a thick plate of glass with our letter R, from part one, etched into it like one of those images in a glass paperweight, like this:

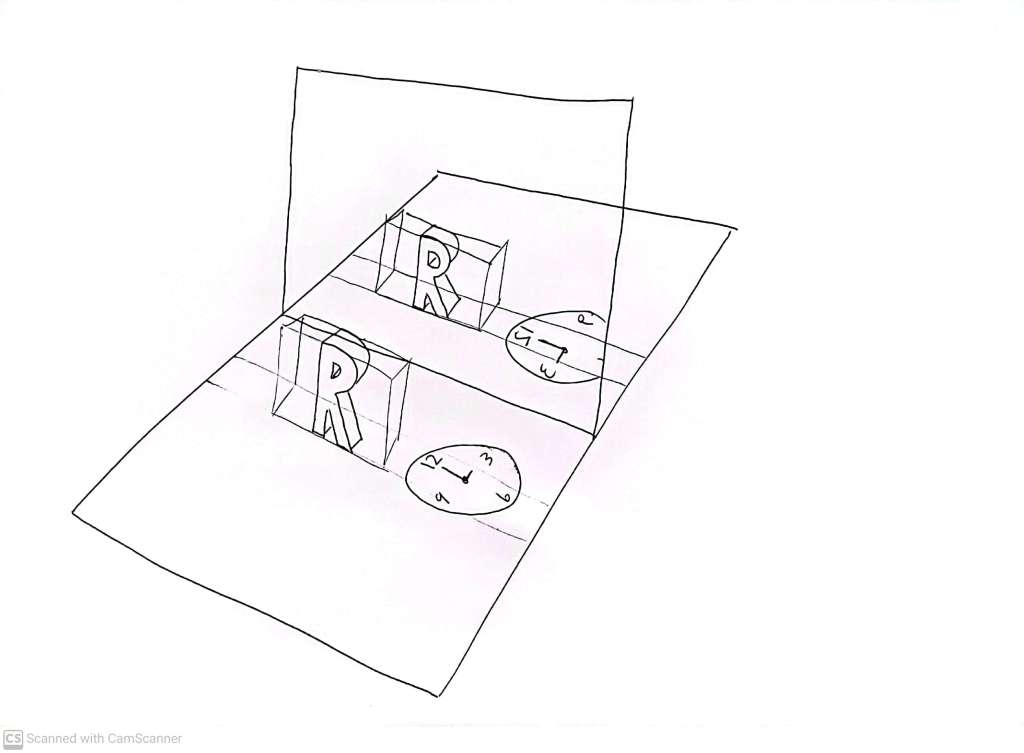

Now let’s put this object in front of a mirror:

The way we have oriented it, the plate of glass is actually exactly the same at all values of the coordinate perpendicular to the mirror. This means that its reflection, as viewed from our godlike perspective, is exactly the same as the original object, and the reflected letter R looks, from our godlike perspective, exactly as it looks in the original room!

You may have noticed that we don’t usually write IN glass. We usually apply ink ON one side of a piece of paper, and if we want to ‘see’ ‘mirror writing’, we turn the inked side of the paper towards the mirror. Think about what these two observers see when they look at the R in the glass:

This is the change in vantage point forced upon us by the inversion of ink and paper, which lie very close to each other, but not in precisely the same plane, and crucially, with the paper obscuring our vision, enforcing the change in perspective.

So, to summarize:

A mirror does NOT flip writing left and right OR up and down. Seen most simply – it flips the layering of the ink and the paper – and forces us to view the writing ‘from the back’, which we are left to interpret as we see fit – usually through our preconceptions of what is up (vs down) and what is front (vs back).

Epilogue

My father began his career as a typesetter in the printing business. Typesetting involves handling a lot of ‘inverted’ letters which have to be arranged on print blocks, so that they produce conventional lettering when ink goes from the face of the typesetting to the face of a piece of paper, which are pointing in opposite directions when they touch. Because of this work, my father can read ‘mirror writing’ (as it appears on print blocks) just about as fluently as he can read normal writing – and he says that it’s easier when you apply the old typesetter’s trick of turning it upside down!