Who doesn’t love Pi. Blueberry, apple, chicken – or the one whose digits you memorize to impress your friends. Even non-mathematicians are known to have some fascination for the number π, the ratio of the circumference of a circle to the diameter of that circle.

No, it’s not 22/7, and nor is it expressible as any finite combination of algebraic operations – generously counting square and higher ‘roots’ as algebraic operations. A transcendental number, it is!

To grind out a (decimal, for example) representation π of with higher and higher accuracy, you need to work harder and harder. The words defining it are logically meaningful, but in terms of generating any numerical specification through algebraic operations, we can only get closer and closer to the truth, without ever fully reaching it.

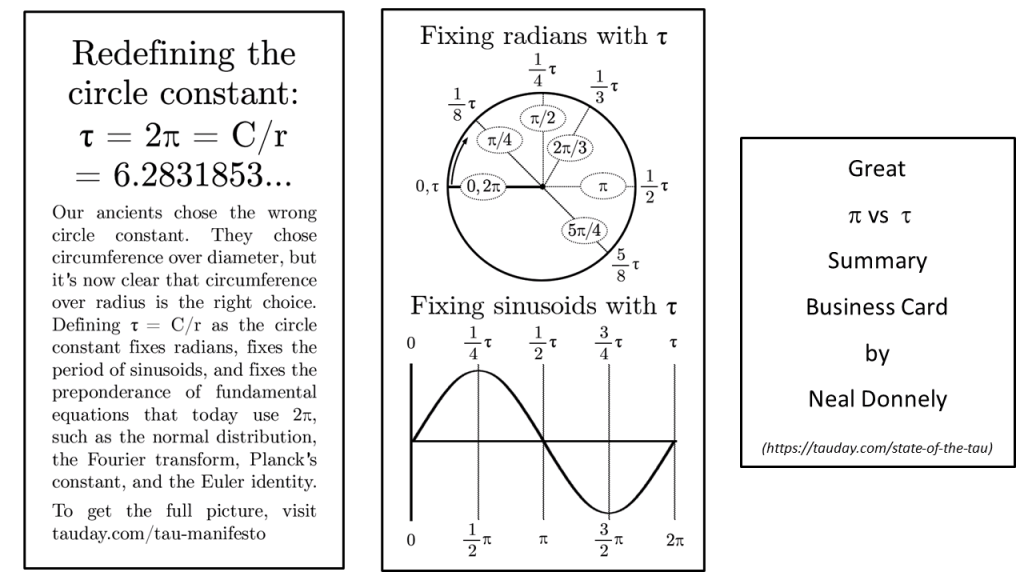

The ‘Circle Constant‘ π comes up in all sorts of interesting places – all ultimately coming back to some reference to a circle – although sometimes the circle in question is not superficially obvious. Even the correctly written ‘normal distribution’ function has a factor of (a square root of 2 times) π in it. In fact, it’s a bit unusual, in applied mathematics, to come across a π that’s not next to a 2. It’s also noteworthy that when we measure angles in ‘radians’ – which is, really, mathematically the only sensible way to measure angles – then a full rotation is an angle of 2π radians. The size of an angle, in radians – is just the ratio of the arc-length (round edge) of a pizza slice, to the radius (straight edge) of the Pie:

At some point, one has to ask the question:

Should we not perhaps have defined some famous named number as the ratio of the circumference a circle to the radius (not diameter) of that circle?

The ratio of the circumference a circle to the radius (not diameter) of that circle is just twice the value of the more famous circle constant π – after all, the radius is just half of the diameter. All the famous formulas that tell us about areas, volumes, and so on, of circles and spheres involve the radius. Not one of these formulas, in its standard form, refers to the diameter. What, after all, is a circle? It is all the points, in a plane (flat surface) which are a particular distance (R) from some reference point O. The O would be the centre of a circle of radius R.

It’s just clumsy and weird to talk about the diameter of a circle – so again: why did we define the famous ‘circle constant’ to refer to the diameter? Why not give a name to the number which is exactly twice π, and give that number a glamorous name, and make a fuss about it.

It’s a longish story. The short answer is – it’s a historical accident. Why do we call the unit of force the Newton, and why is length measured in metres? There are no fundamental reasons for these things. But maybe π is different – maybe it really was a kind of mistake, or, at the very least, a missed opportunity to make some formulas, and ideas, much cleaner and simpler than they are currently made to appear.

A really comprehensive view of this issue is expounded in The Tau manifesto, by Michael Hartl, which argues very convincingly that it would have been much better to introduce a famous constant whose value is twice the value of π – and also argues, compellingly, that calling this number τ (Greek letter tau) would work beautifully on a number of logical, historical, phonetic and aesthetic fronts. We here are certainly convinced.

Because π is approximately 3.14159265 … (more roughly, 3.14 …) it has become a bit of a thing to see the 14th of March as ‘π Day’. The value of the proposed intrinsic circle constant, τ, is about 6.283 … , so how about 28 June for τ day? In fact, there are lots of T Shirts for that now!

Depending on your appetite for detail, you might want to read the whole Tau manifesto yourself, and also other updates on matters τ, at tauday.com, but here are some of my favourite points that it makes.

- If you want to describe an angle which is some fraction of a full turn, or even a multiple of a full turn, for that matter, you get a notation that is highly intuitive, when measuring angles in radians (as mathematicians always do). Half a full turn? ½τ radians. Full turn? τ radians. 4 turns – 4 τ radians, and so on. Engineers are known to simply measure angles in turns in some contexts – so in terms of radians, all you got to do is insert a tau, and you’re done

- There are some famous objections to ditching Pi. One line of argument is to claim that some of the most important and beautiful formulas involving Pi do not, in fact, have a 2 in them, and then, when you rewrite them in terms of Tau, which is 2 times Pi, you get a factor of two appearing where there was none – spoiling these most beautiful formulas, and supposedly arguing against the claim that τ is more natural. Hartl nicely points out how either

- the famous formulas actually have a 2 when you construct them, but it cancels with a totally unrelated accidental factor of two that happens to arise but is normally not discussed, OR

- the formulas actually SHOULD have a factor of 2 (in the denominator – so actually a factor of ½ in plain view) given similar formulas where this half has a known reason, and is expected, to be there, OR

- the formula can be replaced by an even more elegant formula, which also doesn’t have any strange 2’s.

- There are actually shapes, other than circles, which can be said to have a ‘constant diameter’, but there are no shapes, other than circles, which can be said to have a constant radius.

So we should really always talk about a circle in terms of its radius rather than its diameter, because the radius fundamentally makes the circle.

With powerful reasons like this – why does this τ thing not become mainstream? Actually, in recent years, the number of techno and pop culture references are increasing impressively, and τ may well ultimately prevail over π – we sure hope so.